During the Thirty Years’ War, doctors in the Spanish Army of Flanders found themselves dealing with a new disease. They called the mysterious condition mal de corazón, as its sufferers – mostly conscripts fighting a thousand miles from home, for a cause they cared little about – presented as less physically sick than heartsick, racked with longing. In the worst cases they could only be declared roto, broken, and shipped back to Toledo or Seville.

This was in many ways the first modern war: fought in large part by mercenaries and draftees, waged by arbitrary amalgamations of powers, fueled by wanton violence that perpetuated itself. The alienation it planted in the souls of countless Europeans, with its associated psychic maladies, would come to be deeply familiar. Later in the seventeenth century, a Dr. Hofer identified something much like the mal de corazón among Swiss mercenaries serving far from the Alps. Noting symptoms such as fever, uncontrollable weeping, indigestion, and death, he characterized it as a “cerebral disease of essentially demonic cause” and coined a new term from the Greek for “homecoming” and “pain.” Nóstos plus álgos: nostalgia.

Prescriptions of the day included everything from bloodletting to narcotics, though in many cases, the doctor observes, a cure is only possible if the patient can return home and “the yearning [Sehnsucht] can be satisfied.” For some time the main clue to its etiology seemed to be that the disease was especially prominent among Hofer’s countrymen – so much so that it earned the nickname mal du Suisse. A leading theory held that behind it all was a disequilibrium of pressure, like the diver’s bends turned upside down. As Alpine natives who were acclimated to the thin air struggled to adjust to the low country, their blood thickened, their airways caved, and their brains went on the fritz.

That theory soon fell by the wayside as new cases of nostalgia began to crop up everywhere. (According to official records from the Civil War, 5,213 such cases were observed in Union soldiers, 58 of them fatal.) But there was something peculiar about how easily Swiss nostalgics were triggered. In particular there was a folk song, or rather family of songs, the Kuhreihen or ranz des vaches, that had the capacity to inflame the fever in any patient who knew it. This was a simple herding melody, to be played on the alpenhorn or sung extemporaneously with the names of one’s cows, when it was time to gather them home. The farther from home, the stronger the call. On one occasion in the days of Louis XIV a Swiss traveler attended the Paris Opera, and found the music so pretentious that he stood up and bellowed a Kuhreihen to drown it out. (Louis was so moved that he asked the man to perform at Versailles. He demurred, saying that the melody could only be delivered when the spirit moved him.)

Singing the Kuhreihen had already been outlawed in certain Swiss towns, as it was liable to incite a stampede of cattle; now it was outlawed in the Swiss military to prevent outbreaks of homesickness and desertion. But nostalgia by now had become epidemic, the casualties growing exponentially through the power of suggestion, and commanders had to resort to more desperate measures to keep it from decimating their armies. One Russian general threatened nostalgics with being buried alive as punishment for their weakness, and reportedly carried out the threat on more than one occasion.

By the nineteenth century doctors were alarmed to find that the object of their patients’ longing was in many cases receding, transferred from their physical homeland to some more distant and not necessarily material place. It seemed the disease had settled in for good, transforming itself from a treatable, physical condition into a hopeless psychic one – the mal du siècle, in the words of the Romantics. One of these, Alfred de Musset, explained it simply: “The illness of the present century entirely originates from two causes…All that was is not any more; all that will be is not there yet.” As for an immediate trigger, for his generation in France this was a familiar one: the death of a parent, namely Napoleon Bonaparte.

Wherever it was rooted, in the “nostalgic bone” that early anatomists hunted for vainly or in some wound in the soul, this modern affliction seemed always to be most easily aroused by music. And not necessarily human music, as Thoreau found:

This thrush’s song is a ranz des vaches to me. I long for wildness, a nature which I cannot put my foot through, woods where the wood thrush forever sings, where the hours are early morning ones, and there is dew on the grass, and the day is forever unproved, where I might have a fertile unknown for a soil about me.

Gripped by the mal du siècle and immersed in the colossal, aching new sounds of Beethoven and his followers, the Romantics tried again and again to articulate the relationship between music and longing and the “fertile unknown.” In the philosophy of Friedrich Schlegel, music stands alone among its sisters as an “art of longing” – in its highest form a blend of “the heavenly longing and the terrestrial,” so tightly coupled as to be indistinguishable. E.T.A. Hoffmann likewise upheld music as “the only truly romantic art, for it takes the infinite itself as its sole theme.” To its listeners it reveals “an uncharted realm…that comprehensively encircles its empirical counterpart,” in contemplation of which we surrender ourselves to an “inexpressible yearning.”

However prone these writers may have been to bouts of melancholy, they still had access to a great cultural reservoir of faith. For Schlegel the anguish of yearning strengthened character in preparation for spiritual reward, in a process that was not transitory or superficial but essential to human development. Though it may be felt most acutely at the threshold between youth and maturity, true longing persists “uninterruptedly to the end,” remaining “the first, strongest, and purest impulse of the inner man.”

But that reservoir would be drained soon enough by the ultimate parental death. Already preparing to deliver the eulogy, to commemorate the Gotterdammerung – twilight of the gods – was that “tragic poet of the end of all religions,” Richard Wagner.

Years before the apocalyptic debut of the Ring cycle, Wagner had already served notice with his 1865 opera Tristan und Isolde. This was the work that moved a spellbound Richard Strauss to declare “the end of all romanticism,” hearing in its audacious harmonies a sort of spiritual ultimatum – “the yearning of the entire 19th century…gathered in one focal point.” One chord in particular, prominently featured in the opera’s prelude and eventually known just as the Tristan chord – F, B, D-sharp, G-sharp – was so shocking that it would later be blamed for single-handedly launching modern art. It wasn’t just that the chord was dissonant, or that its composer refused to resolve it; it was that it couldn’t be resolved, as far as his contemporaries could see, in any way that made classical sense. Wagner himself, in his program notes, was not shy about explaining the significance of this:

There is henceforth no end to the yearning, longing, rapture, and misery of love: world, power, fame, honor, chivalry, loyalty, and friendship, scattered like an insubstantial dream; one thing alone left living: longing, longing unquenchable, desire forever renewing itself, craving and languishing; one sole redemption: death, surcease of being, the sleep that knows no waking!…[I] let that insatiable longing swell up from the timidest avowal of the most delicate attraction, through anxious sighs, hopes and fears, laments and wishes, raptures and torments, to the mightiest onset and to the most powerful effort to find the breach that will reveal to the infinitely craving heart the path into the sea of love’s endless rapture. In vain! Its power spent, the heart sinks back to languish in longing, in longing without attainment, since each attainment brings in its wake only renewed desire, until in final exhaustion the breaking glance catches a glimmer of the attainment of the highest rapture: it is the rapture of dying, of ceasing to be, of the final redemption into that wondrous realm from which we stray the furthest when we strive to enter it by force. Shall we call it Death?

These effusions didn’t come from nowhere. Wagner had recently fallen under the spell of yet another German thinker, but one of a very different breed. It’s a breed that now, in some ways, might seem quite familiar. Arthur Schopenhauer was anxious and sickly, weird-looking and obsessively vain, highly motivated by sex and deeply contemptuous of women. His father had thrown himself out of the family attic into the adjacent canal when Arthur was a teenager; his social-climbing mother had shortly moved off to a new city, and written her son from there to accuse him of being “unbearable and burdensome.” Her son went on to become a Gordian knot of contradictions: a brilliantly seductive writer and generally obnoxious acquaintance, a man of hundreds of relationships and few if any close ones, a passionately romantic devotee of art and perhaps history’s most influential pessimist. Not coincidentally he poured himself into realizing, through his philosophical work, a vision of such uncompromising purity that it tilted Western thought at a new angle. For Schopenhauer, the sooner we can accept that life is godless and meaningless, a wheel of irrational striving and suffering, the sooner we can embrace our only possible salvation: the dissolution of the will, through nirvana or otherwise. On first discovering these ideas a besotted Wagner would write to Franz Liszt of finding at last a “sedative” which had “helped me to sleep at night…the sincere and heartfelt yearning for death.”

A century later the composer would acquire an unlikely disciple, also with a genius (according to genius Leonard Cohen) for inducing “those incredible little moments of poignant longing in us.” Over the course of the late 1950s and early ‘60s Phil Spector would find himself cast, unwittingly, in a sort of drama-club reenactment of the entire nineteenth century. Liberation, disenchantment, decadence, the search for new modes of transcendence – everything that the Romantics fought for and succumbed to was again at center stage, with the Enlightenment as antagonist replaced by Squareness in all its manifestations. And at a pivotal moment in this drama, as in the original, we hear another piece of music that serves as an apotheosis of yearning.

Both Wagner and Spector have central, yet ambiguous, parts to play in their linked dramas. Both saw themselves unabashedly as prophets, and were annoyed by how few people seemed to get it. Wagner wasted few opportunities to talk up his concept of the colossal, discipline-shattering “artwork of the future.” Yet for later innovators like the French Impressionists, whose movement finally dethroned the Germans’ “late Romanticism” (for lack of a better term), that future had always been a mirage. Debussy famously waved off Wagner as a “beautiful sunset that was mistaken for a dawn” (never mind that one can easily make the case that Debussy is not Debussy without Wagner). The truth is subtle: while the trampling bigness of the Ring cycle would soon be out of vogue, and would in fact be gruesomely stained by its association with Nazism, some of Wagner’s purely musical innovations were transformative. He was a young rabble-rousing anarchist, after all, long before he was a patron saint of the Third Reich.

And he finished strong. His last opera, the Knights of the Grail epic Parsifal – not an opera, excuse me, a Bühnenweihfestspiel (“Festival Play for the Consecration of the Stage”) – debuted when he was nearly seventy and made a splash. Even Debussy conceded it was “one of the loveliest monuments of sound” ever erected. Wagner’s onetime acolyte Nietzsche was disgusted by the master’s reactionary retreat into Christianity, trashing the libretto as “a work of perfidy, of vindictiveness, of a secret attempt to poison the presuppositions of life” – and still wondered aloud whether the music had ever been better. The old man died believing that his sun was still rising.

Spector by contrast had the misfortune to peak at twenty-three, and to be confronted soon thereafter and for the rest of his days by his own obsolescence. By thirty he was already a ghost, sulking over his betrayals by the living and passing out BACK TO MONO pins to anyone who’d listen – a futile crusade against the new sound standards that shockingly forfeited control to any idiot listener in his rec room. Things moved faster now. And the Philles records already felt like they belonged in a museum. In purely musical terms, setting politics and technology aside, as masterfully as they consummated the old, one is hard-pressed to point to anything truly and specifically new. The influence of “Be My Baby,” as we’ve seen, lay more in empowering expression in general than in spreading a particular style of songcraft.

If there is a Tristan chord in pop music, a dawn of disorder, then there’s an obvious contender: the jangling chord that famously rings in “A Hard Day’s Night.” Essentially a combination of F major and G major triads with a D on the bottom, sounded by George’s new Rickenbacker 12-string along with John’s guitar, Paul’s bass and George Martin’s piano, this audacious act is possibly the most recognizable single noise in the history of rock. “A hijacked church bell announcing the party of the year,” it’s been called, but what kind of party exactly?

A party for folks with the blues, it seems. By presenting what will turn out to be the song’s home chord (G) but forcing over it the flat-seventh chord (F) that it’ll return to in the verse, this combination of notes insists on a sort of liberating disillusionment. Daily life for these partygoers is tough, empty, a grind through which we work like dogs and long for the release of sleep. The only other respite is the lover’s embrace, though even that only makes us feel “all right,” most nights anyway. So we might as well dance while we can, in the shapeless modern style.1 Schopenhauer would have approved this message.

It’s a radically different one from that of “Be My Baby” just months earlier. With its seemingly unabashed faith in resolution, in transcendence, in a fertile unknown rather than an encircling void, the latter song is distinctly early Romantic rather than high Wagnerian. We might say that it represents that phase’s beautiful sunset, its final climax. Is there a meaningful parallel to draw? How far can we push this?

Well, there is an early Romantic classical work about which similar things have been said. It happens to be, like “Be My Baby,” one of the very few in its tradition with a serious claim to being the greatest of all time. It also happens to have tormented the imaginations of its successors – including Richard Wagner himself, who called it the “mystical goal of all my strange thoughts and desires about music” – in a way that would be very familiar to, say, Brian Wilson. It’s Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, and before you laugh, let me remind you of what it was like to hear it in 1824.

In short: exhilarating, and confusing. The scale of the thing, with individual movements the length of whole Mozart symphonies, was taxing enough on the mind of the average concertgoer. Many recoiled at the inclusion of a choir – essentially the first time that the human voice had infiltrated the symphony, that temple of absolute music. And then there was the issue of form. No doubt that the first three movements included some of Beethoven’s most beautiful, monumental, and violent music, but confined within something like recognizable classical structures. In the fourth and final movement, when the singers came crowding in, it all seemed to fall apart. Intricate fugues jostled with naive folk melodies; celestial raptures gave way to what sounded like drunken marching bands, often without warning. What sense could be made of this?

If there was broad suspicion that the composer’s genius had at last tipped into madness, the spectacle at the premiere only supported it. Beethoven was determined to conduct his own magnum opus, but there was a small hitch: his hearing was by now all but totally shot. So an arrangement was hastily made in Vienna to let him stand near the orchestra and wave a baton, while the musicians took their real cues from their usual director. As the legend has it, Ludwig inevitably fell behind and went on waving when the music stopped; he had to be gently turned around by a helpful contralto, in order to receive his thunderous applause.

After two hundred years, the debate over the many meanings of the Ninth remains inexhaustible. And yet, unlike every other symphonic composer before him, Beethoven gave us a massive assist by putting actual words to his music. This of course was the “Ode to Joy,” an abridged version of a forty-year-old poem by Germany’s supreme Romantic Friedrich Schiller. We all know it, or think we do; it’s the official anthem of Europe and gets a hearing at every Olympic Games. I remember a commercial during one of these in which David Beckham kicks footballs into kettledrums to sound that unmistakable melody, pounding it into complete banality. If asked what it means, though, most of us may dredge up something like its hymnified text from “Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee” (written by a preacher and Beethoven fan in 1907). The brotherhood of man, marching gaily onward in the light of the Father’s love.

Schiller’s original, which has been called “insidiously subversive” and was attacked for blasphemy in its day, is pretty different. This is a writer who saw organized religion as a tool for oppression, who rejected any literal interpretation of gods, who referred to his time as the “Age of Unbelief.” Instead of fathers and brothers, the Ode begins by invoking another figure:

Joy, beautiful spark of Divinity,

Daughter of Elysium,

We enter, drunk with fire,

Heavenly one, thy sanctuary!

Thy magic binds again

What custom strictly divided;

All people become brothers,

Where thy gentle wing abides…

All creatures drink of joy

At nature’s breasts.

All the Just, all the Evil

Follow her trail of roses.

Kisses she gave us and grapevines,

A friend, proven in death.

Ecstasy was given to the worm…

Who is this? A mother, clearly – but a sexy one! We’re to drunkenly enter her sanctuary and claim our ecstatic birthright? For every kiss we give her, will she give us three? Is it going too far to call this Joy the same voice that narrates “Be My Baby”?

When something like a recognizable Christian God does finally appear, he’s addressed in slyly questioning, subjunctive terms:

Brothers, above the starry canopy

There must dwell a loving Father.

Are you collapsing, millions?

Do you sense the creator, world?

Seek him above the starry canopy!

Above stars must He dwell.

The poem seems to recognize a supreme, benign, creative force – with Joy acting as its earthly agent – and the importance of orienting ourselves to it. But it nudges us to rethink our traditional notions of that force, too. Later in the original text, Schiller grabs Christian orthodoxy right by the collar with the lines “God judges as we have judged” – in other words, He’s only a projection of ourselves, when you get right down to it. Beethoven, who was certainly more of a Christian than Schiller but a long way from orthodox, couldn’t quite stomach including that line in the Ninth. (He also left out a bunch of Dionysian imagery about bubbling cups and foaming wine, which make it clear that the Ode was intended as a glorified drinking song.)

Many have heard in the symphony a depiction of the composer’s own struggles with deafness. Back in 1802 when his fate was first becoming clear, he’d written an anguished letter to plead with”Providence” to “grant me at last but one day of pure joy”; perhaps, over the course of the Ninth, he manages to find it. But it’s equally possible to hear the spiritual struggles of his entire society. The muscular, often furiously dissonant first movement suggests an old-style hero who’s resisting being put to rest; the movement ends with what sounds like a funeral march. Yet in the second movement that same masculine energy now seems to be spreading from the individual across the land in a sort of frenzied dance. This at last gives way to the lovely, placid music of the third, which hints at a sort of Schopenhauerian resignation to suffering.

The final movement opens with what Wagner dubbed the “horror fanfare” (which inevitably sounds better in German – Schreckenfanfare): an awful blast of revulsion at everything that preceded it. Snippets of the first three movements are rehashed, and dismissed one at a time by a group of finger-wagging basses. Then when a voice finally enters, it’s a solitary baritone delivering a plea that Ludwig himself added to Schiller’s text: “O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!” O friends, not these sounds; let’s make more joyful and pleasing ones! Only then does the Ode properly begin. To these ears it sounds as though, consciously or unconsciously, the master anticipated all the perils of the spiritual revolution in which he found himself swept up. Chief among those were the violent hubris of the liberated individual will, and the passive nihilism of a community severed from its sources of meaning. Together these made up an unhinged bipolar reaction to which an alternative, a higher path, must be found.

This path should be a happy, peaceful one, but an active one too. In the remainder of the Ninth’s finale, Beethoven gives us his proposal. At its center is the grand fugue in which he intricately interweaves the two main themes of the Ode: the appeal to the feminine Joy figure, and the invocation of the Creator beyond the stars. The implication is that our various earthly unions and our prayers to the infinite turn out not to be separable. From our striving toward togetherness – not just with our brothers, but with our lovers, our parents, indeed every Worm of creation – a more upward, celestial striving will naturally unfold, and the latter will fertilize the former. What the Ninth calls forth in us is exactly that blend of “the heavenly longing and the terrestrial” which Schlegel, at almost exactly the same time, was presenting as the ultimate aim of all music.

For a lot of people, even in 1824, this kind of rhetoric had the sound of a juvenile fantasy. Schiller himself was mildly embarrassed by his poem when looking back on it from middle age. But Beethoven doubled down on that naïveté, setting the text to a tune so simple it evoked a folk song, then giving it to a stumbling fife-and-drum band to lurch through in between angelic choral exaltations. It sounded vulgar and ham-handed to much of his highbrow audience, who couldn’t understand why he’d tarnish some of his most sublime work with this descent into the streets. One American reviewer scoffed that the Ode reminded him of “Yankee Doodle.”

But for those willing to be transported, willing to buy into a sort of heroic innocence, the Ninth opened a door to ecstasy. At the forefront of these revelers was Wagner, who marveled at the “colossal naivety” to which Beethoven submitted himself in order to deliver us a “vision of agelong bliss.” Others noted the clever machinations by which the composer prepares us for that vision. Dotted rhythms, for example! These work by prolonging notes into subsequent beats to thwart expectation – boom, boom-boom – and are commonplace to us now, but in the classical period were largely the stuff of marches and processionals. Beethoven ladles them all over the place. Listen to the very opening, at the fierce stutter of the first theme, once it coalesces from the cosmic mists of the strings. The tension of those notes is toyed with in a hundred ways over the next 45 minutes, until it finds its last release in the steady drive of the Ode. A few tense passages punctuate the finale, only to build back to climax. And it’s a climax that rocks at times, with a subtle orchestral backbeat that can get you out of your seat if you don’t look out. In essence it’s the same pattern as in “Be My Baby,” the same pattern that Hal Blaine so masterfully channeled: the most ancient one of all.

This is not to suggest that anyone involved in either of these works was thinking dirty thoughts in the process. That said, Spector and Beethoven, to name two, certainly had no shortage of erotic frustration ripe for the sublimating. The latter, forever in love and possibly never in bed, once wrote to one of his countless chaste paramours: “I have resolved to wander about in the distance, until I can fly into your arms, and can call myself entirely at home with you, can send my soul embraced by you into the realm of spirits.” There it is again: the intimation of a synergy between the carnal and the spiritual. We’re jaded to that kind of pillow talk anymore. When you’re lyin’ here in my arms / I’m findin’ it hard to believe / We’re in heaven. But while we may scan it as flirtatious metaphor, the compulsion with which serious thinkers in Beethoven’s day kept circling back to this subject – of longing, and consummation, in their worldly and heavenly forms – suggests that there’s something a lot heavier there.

In writing a tribute to a song from the 1960s, I did not expect to be spending so much time in the 1800s. But I also didn’t expect to be bumping up against the central conundrum of modern existence. When you get there, you’ve got to come to grips with the folks who got there first.

Once we’ve outgrown our fairy tales and our crushes, once we know too much to see the world as magical, how do we hang onto the vitality of youth? Is our flight from superstitious fear into the cool light of reason worth snuffing out the flames of wonder and hope? Does our longing for that lost wildness just amount to a regressive neurosis, or might it suggest that the price really was too high – that those attitudes really were in some way essential to human flourishing?

We pose these questions from and to our collective self, our culture, at times when its figurative adulthood starts to feel oppressive: in response to the obliterating secularization of the Enlightenment, or to the alienating forces of technocratic capitalism. And we pose them individually, as we arrive at and continually wrestle with the disenchanted adulthood of our literal minds and bodies. Our childhoods call to us always from beyond a forbidding wall of modern construction. When we hear a piece of music that maps that forgotten terrain, the questions confront us anew, even if only as a twinge, a stirring.

The longing that “Be My Baby” evokes: maybe now we can figure out what that longing is for. There is something locked in that echo chamber that we are desperate to retrieve. Teenage lust, some would say, and be done with it. But that was not what brought John Lennon to his knees, surely. The song would have spoken to him not only of an ideal lover but of a lost mother, too, a figure under whose “gentle wing” he could shelter and “drink of joy,” to borrow Schiller’s old words.

We all long at some level for both of these, and more. But there is a longing on a different level, a longing for which the word nostalgia was invented. Our struggle to define that word betrays our inability, or our reluctance, to come to grips with the concept.

We discovered that “Be My Baby” not only speaks, but harmonically encodes, a plea for love. But this is not a normal, transactional plea. Remember what was written of Ronnie: that she sings as though “the boy’s returning her love is secondary to her own assuredness.” Remember what was written of Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry: that in their music “no distance divides desire from its object. Gratification is instant because yearning intensely makes it so.” This is a plea for love that validates itself, that fills its speaker with love by the very act of pleading, that somehow places her and us in a state of anguished, but ecstatic, incompleteness. There’s a name for this special appeal, the appeal for which the ice cream changes were expressly built as a vehicle, only to be scuppered at the side of the road as its contents went out of fashion. Remember the very first words that were uttered over those chords, in the ur-text of “Blue Moon”:

Oh Lord, if you’re not busy up there

I ask for help with a prayer

The plea is a prayer. And a prayer is nothing if not a form of ritualized longing. If done properly, prayerful people tell us, it serves as its own justification and reward. It suggests to us that longing doesn’t have to be merely a negative act, a lament, but can be a creative one. Many of us, myself most definitely included, have long since forgotten what sense that makes. But when we hear “Be My Baby” we are moved in that old way. We are forced to recall how it feels, to abase ourselves before the infinite. We long for that longing.

For the Romantics it was still fresh enough in their shared memory that they could discuss it openly. Some still even engaged in it. Samuel Taylor Coleridge thought prayer to be “the very highest energy of which the human mind is capable,” and lamented that so few of his contemporaries were capable of such a thing. Seeking a unified theory of prayer, he broke the act down into five stages: “the pressure of immediate calamities,” “horrible solitude,” “repentance and regret,” “celestial delectation,” and “self-annihilation.” It seems debatable how many supplicants get to step five, but the first four could be used to caption the ice cream changes.

In more recent times you have to turn to “religious writers” to find these attitudes still taken seriously, and even then often only in whispers. Here is C. S. Lewis:

In speaking of this desire for our own far-off country, which we find in ourselves even now, I feel a certain shyness. I am almost committing an indecency. I am trying to rip open the inconsolable secret in each one of you—the secret which hurts so much that you take your revenge on it by calling it names like Nostalgia and Romanticism and Adolescence…Our commonest expedient is to call it beauty and behave as if that had settled the matter…The books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them; it was not in them, it only came through them, and what came through them was longing…For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.

Virtually every modern language has a word attached to this feeling, this sweet, vertiginous melancholy, each just as slippery as “nostalgia”: saudade in Portuguese, hüzün in Turkish, lítost in the Czech of Milan Kundera, who memorably described it as a “feeling as infinite as an open accordion.” Lewis used the term Sehnsucht, cribbed straight from the Romantics, who used it both for authentic, ecstatic spiritual desire and for its displaced latter-day echo. Literally it means something like “longing addiction.” That conjures up a tragic poet wasting away in an opium den, but it’s more than just a colorful turn of phrase. Some thinkers of the period saw true longing not as a simple one-way appeal, but as a sort of chemical bond between the divine and the earthly – not as a passing feeling, but as a force that eternally, compulsively reanimates the cosmos. No one put this more vividly than the philosopher F. W. J. von Schelling (whose career oh-so-helpfully overlapped with that of Schiller and the Schlegels). According to him, Sehnsucht is nothing less than “the longing felt by the eternal One to give birth to itself.”

This may seem like a surprising way to speak of the Creator circa 1809. Schelling was a surprising sort of philosopher: wary of systems, fond of metaphor and allusion, prone to changing his mind. He developed one of the all-time great intellectual rivalries with his old college roommate Hegel, whose work he found obnoxiously arrogant. Among other squabbles, the two parted ways on the capacity of reason. For Schelling that capacity has a hard limit, as the Absolute cannot be grasped by merely thinking about it; only certain forms of intuition can get us there, hence his call for philosophy to “flow back…into the universal ocean of poetry.” For his opponent, on the other hand, capital-R Reason is already in the process of realizing itself as the Absolute – and what’s more, everything in the universe can be put into a logical system that explains that process.

Hegel won, not because everyone agreed with him, but because the sheer weight of his system made it unignorable. Here was plenty of order to keep the gathering chaos at bay. And it succeeded, too, because it aligned nicely with the story the culture was already telling about itself: a hero’s journey, a forward march, out of the wilderness and towards freedom. Maybe freedom was already within our grasp! Hegel’s writings often implied that he was writing the final chapters of history, and that the modern state, already nearly perfected, would get us there. His last lectures reveal some doubts on this subject, and some dim anticipations of the horrors of states to come. But he died, barely sixty, before he could think it through.

With the Establishment thus buttressed by philosophy, Romanticism settled into its posture of resistance. There was little question now that Reason would run the show. As for the infinite, its prevailing image would be either the dead void of the pessimist, or the optimist’s utopia to be methodically penetrated and conquered, instead of a fertile unknown keeping us in a magical thrall.

Resistance needs weapons, and the Romantics’ main task was to weaponize Unreason and wield it against the Enlightenment and all its monstrous offspring. More monstrous than any of its predecessors would be the “Moloch,” christened by Allen Ginsberg, that arose to devour 1950s America. (“Moloch! Moloch! Robot apartments! invisible suburbs! skeleton treasuries! blind capitals! demonic industries! spectral nations! invincible madhouses! granite cocks! monstrous bombs!”). Battling this beast, Ginsberg’s guerrilla Beats adopted spontaneous expression as their key tactic.

But this was nothing new, even to their Romantic forebears. The poet makes his debt plain in his dream at the end of “Howl,” in which we all wake from our benumbed state and return our oppressor’s fire with “angelic bombs” dropped by “our own souls’ airplanes roaring over the roof.” This is language borrowed from the dreamers of a very different place and time, a world the Enlightenment thought it had buried. It’s the language of the mystics, who for millennia already had been seeking sparks of life in a deadened world, and it’s with them that we have to grapple next.

If you’re into hot longing, there is none hotter than the longing that sizzled up from the medieval cloister. We’ll hear more, but a selection from Mechthild of Magdeburg will set the stage. “The bliss of the angels makes me ache with love,” she has her personified Soul declare, “if I don’t see their Lord and my bridegroom.” At last she’s allowed to do so:

And so [the Soul] goes to the most handsome in the secret chambers of the invisible Godhead. There she finds the bed of love and the room of love made ready, not in a human way, by God. Then Our Lord says: “Stop, Lady Soul!” “What is Your command, Lord?” “You should undress yourself!…you should strip yourself of both fear and shame and all external virtues; only those which are innate should you nurture eternally: that is your noble longing and your boundless desire. These I shall satisfy eternally with my infinite generosity.” “Lord, now I am a naked soul and You in Yourself a richly adorned God. Our communion together is eternal life without death.” Then a blessed stillness follows that they both desire. He gives Himself to her and she herself to Him…

Though this sort of talk reached full flower in the Gothic thirteenth century inhabited by Mechthild, it runs all through the history of Christianity. At one end we find St. Augustine himself being “set on fire” with longing for God, and concluding paradoxically that such desire is the way to dwell in God’s love. (“I tasted you, and now I hunger and thirst; you touched me, and I burned for your peace.”) At the other end there is Kierkegaard, recoiling against Hegel and defending an erotic, inherently endless straining toward truth. Here we find the Augustinian paradox reframed again: “the more [a human being] needs God, the more deeply he comprehends that he is in need of God, and then the more he in his need presses forward to God, the more perfect he is.”

Of course this is hardly peculiar to Christianity. Even limiting ourselves to the other major Western religions, expressions of holy desire are easy to find, especially in the late Middle Ages. “What is the proper form of the love of God?” asked the Jewish scholar Maimonides, and answered himself: “It is that he should love Adonai with a great, overpowering, fierce love as if he were love-sick for a woman and dwells on this constantly.” Around the same time, in explaining his mystical strain of Islam, the poet Rumi declared that “a Sufi is someone whose heart has been broken.” He elaborated on this in his masterwork the Masnavi, comparing the mystic to the reed cut from the reedbed, hollowed out with fire and played as a flute. The song that emerges expresses a longing for return, but again, a special, blessed, self-fulfilling form of longing:

Every thirst gets satisfied except

that of these fish, the mystics,

who swim a vast ocean of grace

still somehow longing for it!

No one lives in that without

being nourished every day.

What was it that welled up in the collective unconscious during this period, spurting forth everywhere in effusions of love? In Europe the herald of this new sensitivity was St. Bernard, abbot of Clairvaux, a multifaceted figure so compelling in his day that Dante tapped him as his guide through Paradise. Bernard is maybe best remembered for whipping his countrymen up for the Second Crusade, but he was a love poet, too, in his own way. In this thoroughly Romantic passage from one of his sermons, Bernard confesses to – well, a longing for longing:

During my frequent ponderings on the burning desire with which the patriarchs longed for the incarnation of Christ, I am stung with sorrow and shame. Even now I can scarcely restrain my tears, so filled with shame am I by the lukewarmness, the frigid unconcern of these miserable times…I pray that the intense longing of those men of old, their heartfelt expectation, may be enkindled in me by these words: “Let him kiss me with the kiss of his mouth.”

The old abbot would no doubt be even more depressed by these modern times, which by his thermometer are tepid indeed. His yearning to be ravished by Christ is an urge that strikes most of us as extremely alien, and tough to square with our image of a man with a tonsure. Certainly this kind of language is a far cry from the Bible.

But there is a place in the Bible where it finds voice – albeit just barely, as its place in scripture is strange and fragile and perennially contested. It happens to be the book on which Bernard was sermonizing, and the book which he was directly quoting, when he issued that plea for a kiss. I’ll let him introduce it:

But there is that other song, which, by its unique dignity and sweetness, excels all those I have mentioned and any others there might be; hence by every right do I acclaim it as the Song of Songs. It stands at a point where all the others culminate. Only the touch of the Spirit can inspire a song like this, and only personal experience can unfold its meaning. Let those who are versed in the mystery revel in it; let all others burn with desire rather to attain to this experience than merely to learn about it. For it is a melody that resounds abroad by the very music of the heart, not a trilling on the lips but an inward pulsing of delight, a harmony not of voices but of wills. it is a tune you will not hear in the streets, these notes do not sound where crowds assemble; only the singer hears it and the one to whom he sings – the lover and the beloved.

Every Romantic, it seems, must have his or her own Song – the piece of art that touches us in our deepest, darkest place, sets us pulsing with delight. For Bernard this was the Song, the Song of Solomon, the black sheep of the Old Testament. He obsessed over it like Brian Wilson over the Ronettes. The sermon above was one of eighty-six that he wrote about this single book – and he only made it up to chapter three.

The “Song of Songs, which is Solomon’s” crashes the biblical party like a stripper at a wake. If you’re reading the Good Book in order you’ve just read the end of Ecclesiastes: “The end of the matter; all has been heard. Fear God and keep his commandments, for this is the whole duty of man. For God will bring every deed into judgment.” Then you turn the page to what appears to be a medley of smoky love songs, which somehow gets away with failing to mention God even once. You hear a man portraying his lover as a locked garden overflowing with fountains and frankincense and pomegranates. You hear a woman fantasizing about hearing her lover knock at her door, and arising, naked and “dripping with myrrh,” to let him in. “Be drunk with love!” the chorus exhorts.

Maybe King Solomon had something to do with it, but then why does the first speaker, and the primary speaker, sound more like a teenage girl? And why does she sound like she belongs more in 1963 than in 900 BCE? This is a young person who knows more than a thing or two about sex, who wanders the streets of her city getting in trouble, talking back to older brothers and policemen. She’s even got a girl group, a gaggle of background singers whom she dubs the “daughters of Jerusalem,” chiming in behind her now and then. And how on earth did this work its way into the Hebrew canon?

That last question has caused all sorts of scholarly gymnastics over the centuries, but the Official Answer has always been that the Song is one big allegory – of the “marriage” between Yahweh and Israel, or God and the Church. The only thing really being consummated here is the renewal of the covenant. Interpret it any other way at your peril, the early rabbis warned (“Whoever warbles the Song of Songs at a wedding banquet…has no share in the Age to Come”). We can laugh at their denial, but we should be grateful, too, for otherwise the work would have gone the way of all other ancient Hebrew love poetry. And even some of the rabbis admitted that the Song was ultimately mysterious – a locked door, to paraphrase one of them, to which we’ve long since lost the key.

Some new keys have turned up in recent years. In particular, the Song turns out to sound a lot like certain other poems we’ve found. They are not Hebrew. Astoundingly, they were written some thousand years before Solomon even, and hundreds of miles distant. Listen:

His left hand is under my head, / and his right hand embraces me! (Song 2:6)

You are to place your right hand on my genitals while your left hand rests on my head, bringing your mouth close to my mouth, and taking my lips in your mouth: thus you shall take an oath for me. (Dumuzi-Inanna B)

Your lips drip nectar, my bride; / honey and milk are under your tongue (Song 4:11)

Man, let me do the sweetest things to you. My precious sweet, let me bring you honey. In the bedchamber dripping with honey, let us enjoy over and over your allure, the sweet thing. (Šu-Suen B)

A garden locked is my sister, my bride, / a spring locked, a fountain sealed. / Your shoots are an orchard of pomegranates / with all choicest fruits (Song 4:12-13)

My shaded garden of the desert…my first-class fruitful apple tree… (Dumuzi-Inanna E)

These other poems come to us from the great cities of Mesopotamia, where they were pressed by reed styluses into soft clay, and baked hard for posterity. They are among the first literature we know of in the world, and on the subject of love, they are the first. Unlike the anonymous lovers of the Song, their protagonists have names. Who are they?

Dumuzi, as the story went, was a real-life king of the city of Uruk who was granted immortality and entered the Sumerian pantheon as a god of shepherds. But it is his beloved who is really at center stage here. The goddess Inanna is a figure of overwhelming importance. For long stretches of history she was the most powerful and beloved deity of the world’s first great civilization. When the first known author put her name on a work of literature – a woman, Enheduanna, daughter of King Sargon of Akkad – that work was a hymn of praise to Inanna. When a new king ascended the throne (as did Šu-Suen, the subject of the second poem above), he had to get the goddess’s blessing in the most intimate way: by assuming the role of Dumuzi and consummating the sacred marriage all over again. (Whether this was done symbolically or actually, physically, with a priestess representing Inanna, remains a delicate question.) The goddess had in her keeping the mes, the divine laws that undergird civilization, and she must be propitiated for her people to remain civilized.

There’s some irony there, because to the modern reader Inanna is not a civilized god. One of her domains is war, a context in which she can be savagely ferocious. More fundamentally, though, and not coincidentally, she is the goddess of sex. Not “love,” as we understand it; not “fertility”; sex. She has no children, but endlessly celebrates her own vulva, comparing it to a fertile field and wondering who will “plow” it (a job for which Dumuzi eagerly volunteers). She pleasures herself; she makes love in varied, graphic ways. And while she glorifies female sexuality in a more spectacular style than virtually anyone who came after, it’s clear that she also holds the keys to sexuality and gender as a whole. One of her hymns attributes to her the power to change women into men and vice versa, and it’s not at all clear that that’s a bad thing. Among her mortal retinue was an order of male priests who wore women’s clothes and, if we’re reading the texts right, were noted for anal sex.

All of this would be greatly watered down over the ages by the euphemisms of embarrassed translators, and Inanna herself would be watered down as she made her way around the Fertile Crescent and across the Mediterranean, incarnating as Ishtar to the Babylonians, Astarte to the Canaanites, Aphrodite to the Greeks, and in subtler forms even long thereafter. But her undeniable centrality in Mesopotamian culture suggests a perhaps uncomfortable idea: that for the forefathers and foremothers of civilization as we know it, sex might have been the most sacred and powerful force in the cosmos – and it might have belonged, in some sense, to the woman.

This idea did not die quietly. Inanna was still very much alive in the times and places of the authors of the Old Testament, and throughout those books we see signs of the struggle against her influence. Eve herself can be read as an inversion of the goddess, since in one myth Inanna first discovers sex (and attains her powers) by sampling the fruit of a forbidden tree. Later on, as the kings and prophets of Judah wring their hands over their people’s faithlessness towards their Lord, it’s clear that two old Canaanite deities stand out among Yahweh’s competition: Astarte (the direct descendant of Inanna), and the related mother goddess Asherah. King Solomon himself is retroactively chastised for having worshiped the former, and a cult devoted to the latter, it becomes clear, was tolerated among the Hebrews for hundreds of years. People installed decorated trees or carved poles in her honor across the land; for some time an Asherah statue stood in the temple of Jerusalem. There’s even the recent bombshell find of a pot in the Sinai desert, sporting a portrait of two figures – one with a prominent penis – labeled “YHWH and His Asherah.” What might have been!

Eventually the tolerance runs out, and around 600 BCE King Josiah tours the country smashing every Asherah pole he can find. Shortly thereafter the Babylonians arrive to raze the temple and carry off the Judeans, leading Yahweh’s people to a crisis of belief. It’s old Jeremiah, the weeping prophet, who concludes that the horrors of captivity are punishment for their idolatry, for heeding the siren song of the false gods, whom Josiah had done his best to stamp out but failed. In one passage Yahweh tears into the exiles, asking through Jeremiah whether they’ve forgotten “the evil of [their] fathers,” and vowing to punish them “with the sword, with famine, and with pestilence” unless they repent. To these impressive threats the Hebrews respond with remarkable pluck. The first to step up, tellingly, are “all the men who knew that their wives had made offerings to other gods.” Soon the women speak up for themselves, and the message is: no thanks.

As for the word that you have spoken to us in the name of the Lord, we will not listen to you. But we will do everything that we have vowed, make offerings to the queen of heaven and pour out drink offerings to her, as we did, both we and our fathers, our kings and our officials, in the cities of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem. For then we had plenty of food, and prospered, and saw no disaster. But since we left off making offerings to the queen of heaven and pouring out drink offerings to her, we have lacked everything and have been consumed by the sword and by famine.

“The Queen of Heaven” is how Inanna had introduced herself; it may even be the literal meaning of her name. She was associated with the planet Venus from the start, the radiant star whose periodic disappearance paralleled her celebrated descent into the underworld. That association casts a new light on an odd verse that seems to be randomly spliced into the Song of Songs:

Who is this who looks down like the dawn, / beautiful as the moon, bright as the sun, / awesome as an army with banners?

One more thing, about that descent into the underworld. It’s the most famous tale from Sumerian mythology, and a clear influence on later plots like those of Odysseus and Persephone. You know it, or part of it, if you’ve read The Golden Bough, in which comparative mythologist James Frazer controversially connects the dots between Dumuzi (Tammuz) and Jesus – demonstrating, with the help of various other ancient myths, our continual return to the image of a resurrected body as a promise of the renewal of life.

Dumuzi does indeed come back from the land of the dead, striking a deal like Persephone to spend half the year there, and thus kickstarting the turn of the seasons. But he is not the protagonist of this story. It’s Inanna who goes down first, willingly, in a power play to extend her domain. Her sister Ereshkigal, merciless queen of Hades, welcomes her by stripping her naked and hanging her “corpse” on a hook. Inanna escapes when the other gods dispatch two trickster spirits to rescue her, but she is tasked with finding someone to take her place. When she comes across her husband Dumuzi, lounging carelessly on her throne with some slave girls, she knows right away who the victim will be. He wails and pleads to no avail; the demons drag him down, and Inanna and her sister finalize the seasonal arrangement. To put the pathetic husband at the center of this myth is to perform another erasure.

To draw out these parallels is not to accuse the Judeo-Christian architects themselves of anything sinister. The themes here are ageless themes, questions that emerge from the deepest bowels of human experience. It would be shocking if they didn’t bubble up organically in each of the great traditions, and if any such tradition failed to build where it makes the most sense to build, atop the ruins of its predecessors. What’s remarkable are not the continuities themselves, but our own surprise at discovering them. That surprise speaks to how aggressively the biblical authors, like the crusading Josiah they depicted, fought to smash the old icons and erect something truly new in their place.

And the examples above should make it clear what that something was. Erect is the right word, because the big idea that arose in Israel and eventually conquered our world was in effect an ivory tower: a brash thrust upward from the swamps of animality. It wasn’t enough for Yahweh to vanquish Ba’al and the myriad other sky-gods of the Near East. Yahweh had to stand alone, the sky god had to be everything, in order for his people to soar above the manifest horrors of earthly existence. That meant purging the collective mind of sex, above all, since it is sex that most constantly threatens to drag us back down into the miasma. And since it was woman who controlled sex, since it was woman who was tied most tightly to the earthly rhythms, since it was woman who held us in thrall to her cavernous secrets, it followed that the goddesses must go if we were to rise above and see the light.

But you can’t just pull the plug, it turns out. The goddesses are not symptoms of a curable weakness in the human condition; they will go on sprouting anew as long as we are human. So it was that even the loathed Astarte/Inanna found a way not only to appear, but to be honored, in an extremely sexy way, at the heart of the Old Testament.

At around the same time that the Song of Songs was likely compiled in its final form, that sneaky minx was also finding her way into the inner circles of power in Rome. Of course she was already there, in the guise of Venus, but she had long since lost her authority; Jupiter, the Romans’ own take on a thunderous, judgy sky god, reigned supreme. But the fragility of that arrangement was exposed by an amazing turn of events in the late third century BCE.

These were dark days for the Republic. War with Carthage was at full boil, and the arch-enemy Hannibal and his brother had stormed into Italy from both ends, putting the capital under the most serious threat it would weather for centuries. Making matters worse, the omens were bad: the last harvest had been a lousy one, and most disturbingly of all, “showers of stones” (i.e., meteors) were being reported every which way.

In these situations the superstitious Romans had one recourse. Stored in the Temple of Jupiter was a set of sacred texts, originally believed to have been dictated by the oracular sibyls of Asia Minor, and hand-delivered by a mysterious old crone (perhaps a sibyl herself) to the last King of Rome centuries prior. In those Eastern ciphers could be found the answers to the most dire questions, questions that were only asked a few times in a generation. With Hannibal and the meteors descending, the books were fetched. Fortunately, the prescription for the ailing Republic was clear. A new god must be found – that is, literally, physically procured – and the sibyl had even specified which one: the Magna Mater, Great Mother, of Pessinos, in Phrygia.

This goddess was also known as Cybele. She dwelt on a mountain, had been raised by lions, and encouraged drunken orgies and a gender-bending priesthood. She was believed to mediate between the living and the dead. Her links to Inanna are not hard to trace. In a convenient twist, she took physical form not as a monumental statue but as a smallish, black stone, thought to be a meteorite. This was what the Republic sent a party to retrieve.

When they at last returned to Rome with the stone in hand, after a long sea voyage and some questionable diplomacy, the whole city turned out to greet its savior. A line of “the leading matrons of Rome” was assembled, standing ready to pass the talisman by hand into the capital. And in case there was any doubt about the centrality of the feminine in all this, one more sign was provided. The ship unexpectedly ran aground on a sandbar in the Tiber, and with the plan in disarray, a matron named Claudia Quinta stepped forward. Claudia was a Magdalene figure with a certain reputation, a woman whose virtue was much gossiped over in the streets of Rome. But filled with the power of the goddess, she managed to free the vessel and tow it single-handedly up the river – an act which ensured her effective sainthood for generations to come.

Cults came and went in Rome, but the Magna Mater was not going anywhere. Five hundred years later, a young St. Augustine would be greeted in the streets of Carthage by a procession of her eunuch priests, the heirs of the temple of Inanna. His revulsion at this parade, at their “anointed hair, whitened faces, relaxed bodies, and feminine gait,” would stay with him for life. In his treatise The City of God he would declare that the Great Mother had “surpassed all her sons, not in greatness of deity, but of crime.” Her greatest crime? Inflicting “the loss of members on men” – a violent muddling of sex to be abhorred not because it’s unnatural, but because it’s all too natural in its savagery.

The aim of the Christian, Augustine reminds us, is to be “purified from mundane defilements.” In all his works we see his strain to rid himself of fleshy excess, “puddly concupiscence” as he memorably puts it. There is a direct line to be drawn between his shame at the first involuntary erections of his youth (celebrated by his dad, met with “trepidation” by his mom) and his construction of the doctrine of original sin. He visualizes the sins themselves as bloatings, swellings, that keep the soul from sliding into the Truth. He would not have appreciated the cascading folds of the Venus of Willendorf, or of the Great Mother of the statuettes from Çatalhöyük.

It’s not a huge surprise to learn that Augustine’s own mother, St. Monica, was an enormous and complicated presence in his life. When he announced at around thirty that he was leaving Africa for Rome, she clung to him weeping, expressing an urge that Augustine identified as a female, physical longing, a carnale desiderium: “with groans she searched for what she had given birth to with groans.” Later in a move worthy of Bertha Spector, she followed him to Europe, broke up his longtime love affair, and set him up with a respectable arranged marriage. Her son was left with his heart “wounded and bleeding,” even as he willed himself to view his lust as a hideous encrustation on the soul.

But then it’s together with Monica that he has the most mystical experience of his life. They’d stopped over at Ostia at the mouth of the Tiber – oddly enough, right at the spot where the Magna Mater had arrived from the East – en route to his new priestly appointment in Africa. Lost in conversation while gazing out a window at a garden, the pair suddenly felt themselves lifted above their bodies and minds towards “that Wisdom by whom all things are made.” At last, after “speaking and panting for it” – where the it is really a her, the feminine Sophia – “with a thrust that required all the heart’s strength, we brushed against it slightly.” A few days later, Monica was dead. Would that ecstasy have been attainable by Augustine alone? We’ll never know.

This tormented ambivalence toward the feminine led the medievals to some strange places. Some of them the modern mind truly cannot fathom, as with the sheela-na-gigs carved over the doorways of dozens of Romanesque churches. These are little women, some smiling and cartoonish, some scowling and monstrous, who reach down to expose their oversized vulvas to the viewer. Are they meant as guards against evil? Cautions against sin? Sneaky homages to a pagan mother goddess? Or just as reminders of the cathartic power of bodily humor? (There are very similar ancient images of Baubo, the Greek character who cheered the grieving Demeter by flashing her naughty bits.) The first, apotropaic hypothesis has the most weight behind it, and it’s significant that medieval pilgrims often sported talismanic badges with phallic or vulvic designs. But the answer could well be all of the above. The body of the Middle Ages was a door to which we’ve lost the key. What is clear is that the genitals had a power then that now seems foreign – that in that world female sexuality was a more visible, active presence than it would be for a long, long time thereafter.

Constantly in those days we hear about penetrating, nursing from, and uniting with the body of Christ. For women this could be a way of identification, as when Marguerite of Oingt describes the “labor pains” of the Passion and lauds Jesus for having given “birth to the whole world.” For men the side wound suffered on the cross (and inflicted by the Holy Lance) became a particular locus of fascination – interpreted by some as the aperture through which the entire Church had been birthed. Flip through a medieval prayer book and you might be startled by an image of that wound as a giant, disembodied, unmistakably vaginal slit. Some of these illustrations in surviving manuscripts show the signs of considerable rubbing over the years.

Small wonder given the fantasies that were enacted in works like the Stimulus Amoris (“The Prickynge of Love” in its English translation), a popular thirteenth-century devotional. Its Franciscan author pushed the maternal-Christ image to its breaking point, concluding of his savior that “He must then, like a mother, feed me with His breasts, lift me up with His hands, hold me in His arms, kiss me with His lips, and cherish me in His lap.” Later on all the wonders of the feminine flesh are even more graphically mingled:

O most loving wounds of our Lord Jesus Christ! For when on a certain time I entered into them with my eyes open, my eyes were so filled with blood that they could see nothing else; and so, attempting to enter further in, I groped the way all along with my hand, until I came unto the most inward bowels of His charity, from which, being encompassed on all sides, I could not go back again. And so I now dwell there, and eat the food that He eats, and am made drunk with His drink.

While a gender-flexible Christ loomed large in the dreams of repressed ascetics, there was also a more conventionally female figure available for worship. Thus in the works of Bernard of Clairvaux we’re suddenly greeted again by the ancient phrase “Queen of Heaven”; now, though, and without irony, it refers to the Virgin Mary. St. Bernard’s devotion to his queen was overwhelming, and decidedly physical. In his definitive miracle, the Virgin appeared to him, exposed her breast, and lactated into his mouth to endow him with wisdom and eloquence. The Lactatio Bernardi is shown in some artworks as a few demure drops, in others a powerful spray from across the room.

The incredible efflorescence of the Gothic period that followed, much of which a conflicted Bernard rejected as “ridiculous monstrosity,” can be seen as one giant hymn to Mary. Chartres Cathedral, to many the genre’s crown jewel, was built to house the Virgin’s tunic – salvaged from the Holy Land by way of Charlemagne and the Byzantine Empress – and to accommodate the throngs of pilgrims that came every year to behold it. But the staggering communal labors that raised all the great Gothic buildings – Our Lady of Paris, Our Lady of Amiens, Our Lady of Reims – are unimaginable without an all-consuming devotion to the Queen of Heaven.

The historian Henry Adams toured the cathedrals around the turn of the twentieth century, and came away reeling from what struck him as the evidence of an entirely separate religion. Interpretations of Mary worship as a mere side-shoot of Christianity, he realized, couldn’t fully account for the late-medieval outpouring on her behalf, amounting to a collective dedication of resources that by any modern economic standards are insane. Chartres and its spectacular companions, in Adams’ words, laid bare “an intensity of conviction never again reached by any passion,” aimed at a figure who “remained and remains the most intensely and the most widely and the most personally felt, of all characters, divine or human or imaginary, that ever existed among men.”

This is big talk, but it gets bigger. Adams observed that the veneration of the Virgin went far beyond anything that could be justified by Christian orthodoxy, and wondered why that might be. For one thing, the image of an endlessly forgiving Mother was an enormous solace to a people terrorized by images of Hell, a people who believed that any weakness might send them tumbling down the pitiless ledger of a God who demanded order. In the words of the medieval philosopher Peter Abélard, “all of us who fear the wrath of the Judge, fly to the Judge’s mother, who is logically compelled to sue for us, and stands in the place of a mother to the guilty.”

There was something more, though. The Mother held within her a mystery which the Gothics sensed was central. To enter one of her great sanctuaries – to make your way between the raised legs of its twin towers, through the vaginal gate of its pointed arch, into its dark, ribbed, magical wombspace – was to travel upstream, beyond history, to the ultimate chthonic source. Henry Adams doesn’t say any of this. But he does go so far as to say that “the proper study of mankind is woman” – by which he means the divine feminine, whose representatives he identifies as Astarte, Isis, Demeter, Aphrodite, and “the last and greatest deity of all, the Virgin” – and that, “by common agreement since the time of Adam, it is the most complex and arduous.”

The study of Our Lady, as shown by the art of Chartres, leads directly back to Eve, and lays bare the whole subject of sex…These questions are not antiquarian or trifling in historical value; they tug at the very heart-strings of all that makes whatever order is in the cosmos. If a Unity exists, in which and toward which all energies centre, it must explain and include Duality, Diversity, Infinity – Sex!

You can imagine the reaction of the patriarchy to any whiff of this line of thinking. If the thrust of history was to be maintained, these backwards impulses would have to be snuffed out. Some of this work fell to Renaissance scholars like Giorgio Vasari, who attacked Gothic architecture as though it were the Devil itself. “May God protect every country from such ideas and style of buildings!” he cried, denouncing that style as a “monstrous and barbarous” one that “sickened the world.” (In fact it was Vasari that introduced the pejorative term “Gothic,” implying that the cathedrals assault our senses, which yearn for classical order, like barbarians assaulting Rome.) But he shows his hand most clearly just further on, in heaping scorn on the medievals’ obsession with concavity, on the “little niches” that seem to proliferate everywhere in their work. Riddled with holes, he complains, “the whole erection seem[s] insecure.”

Culture begins with a big vulva and a blues melody.

We’ve done a lot of bouncing around history, but we haven’t yet traveled back that far – as far as the very first artists (that we know of). These people lived in and around a cave called Hollow Rock, Hohle Fels, which is now a little ways out of Stuttgart on the autobahn, but at the time sat in a windswept tundra with woolly rhinos in the yard. From the human detritus in that cave, dated to around forty thousand years before the present, archaeologists have uncovered two truly mind-blowing objects.

One is the first known representation of a human being. The “Venus of Hohle Fels” is a woman carved lovingly from a mammoth tusk, a woman and a monument of womanhood, with mountainous breasts, massive, canyoned genitals, and a little ring in place of a head, suggesting her use as a pendant. Though she’s easily read as an icon of fertility, there are plenty of other interpretations: according to one, the Venus’s decorations and exaggerations are just those that would have been highlighted by a female carver processing her own pregnancy, or perhaps a stillbirth. Either way, one can’t help but infer that the female body stirred incomparable wonder in the creatures first capable of such a feeling.

The second object is the hollow wing bone of a griffon vulture, with five holes neatly punched along one side. Its purpose is obvious even now: it’s a musical instrument, and the first one known, though its sophistication must place it in a long, unseen tradition. Blow across the top and cover the holes in succession and you get the notes: C, E-flat, F, G, B-flat. A proper pentatonic scale. Its Cro-Magnon owner had already unlocked the Pythagorean secrets, and could have performed, say, the chorus of “Let It Be.”

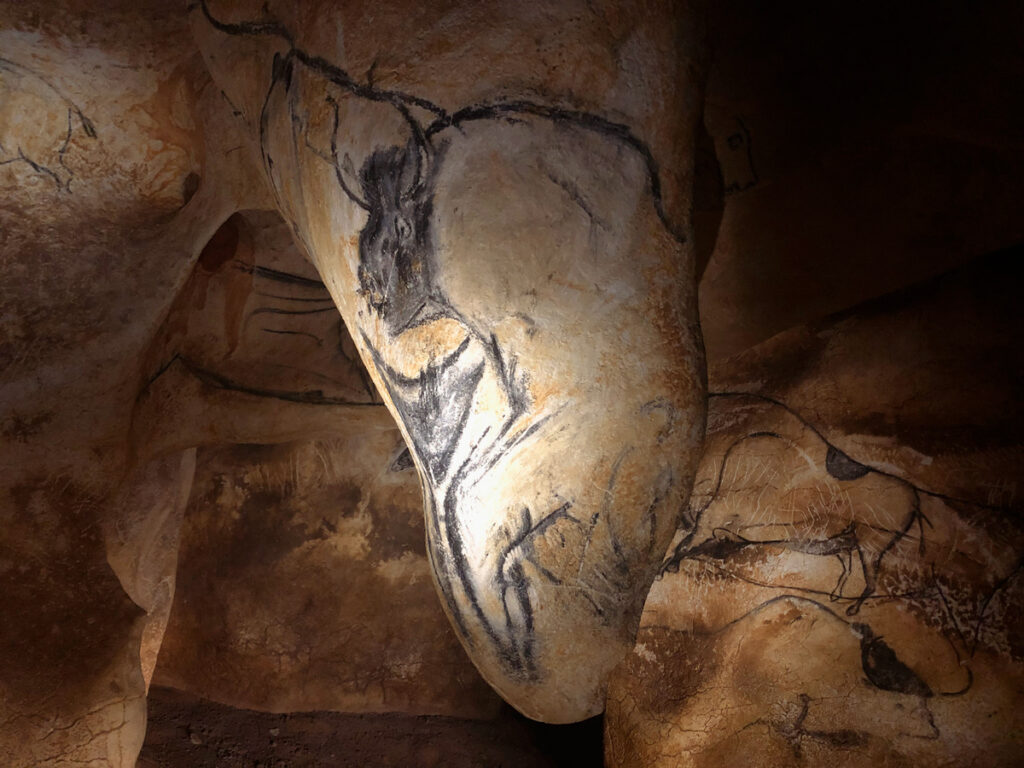

A few millennia later and a few hundred miles to the southwest, some cousins of theirs created arguably the greatest cultural treasure of the whole Ice Age. Unlike the artists behind the ivory figurine and the bone flute, the painters of Chauvet Cave had to undergo a daunting journey, both physically and perhaps spiritually, just to do their work. Chauvet stretches for a quarter mile into the side of a mountain, and was accessed by a single modest entrance that would eventually be sealed off by a landslide for twenty-five thousand years. Armed with torches, supplied with red ochre, and possibly fortified by shamanic mushrooms, these voyagers would have stepped over the bones of cave bears on their way into the heart of that colossal echo chamber. There they proceeded to cover the walls with paintings so exquisite that they shattered our assumptions about the timeline of Paleolithic art.

Virtually all of them were either abstract patterns or startlingly realistic animals – horses, cheetahs, hyenas, owls, the creatures whose spirits you’d most want to channel. But for the giant stalactite guarding the passageway into the deepest chamber, they chose a very different subject. This is a Venus of a more fantastical design: a stark black pubic delta with two stylized legs attached, tapered to follow the curve of the rock, and interwoven with the bodies of a bison and a lion. The earthy strength of the former and the predatory force of the latter seem to flow electrically into the feminine outline. She is the only human to be seen in Chauvet Cave. Like the sheela-na-gigs of the Romanesque, this was the most powerful image its creators could summon to confront those seeking entrance to their most sacred space.

This culture belonged to the first members of Homo sapiens to make their way into Europe, driving their Neanderthal neighbors to extinction in the process. Their blossoming powers of imagination were their greatest weapons. Though finds like those at Hohle Fels are only arbitrary snapshots, they speak volumes about what these people spent their time imagining. The intertwined magics of love and creation, and the uncanny spell of organized sound over the mind and body: these were the things worth thinking about, when thought could be spared from the business of survival. This should be validating for any modern humans who might be wondering why a song sung by a woman, about the making of love, stirs something in their deepest chambers.

That we have to dig for it says much about the cultural landslide that has unfolded since the dawn of recorded history. The time between the Venus of the Cro-Magnon caves and the Inanna of Sumerian poetry dwarfs, by a factor of ten, the time we’ve spent in the care of a male sky god. In the big scheme of things his coup was accomplished in the blink of an eye, before we knew what was happening. Like Napoleon’s it took place amidst the fallout of a revolution: the revolution that replaced basecamps with cities, meadows with wheatfields, oral performances with written symbols, horizontal bonds of kinship with hierarchical systems of control. The new imperial authority was enthroned atop the hierarchy, the all-seeing sun above the highest head, instead of the all-feeling earth beneath the feet. This was a god built for division and conquest, dreamed into life by a people empowered by abstraction and distinction; a god built for the reassembly of human societies into engines of progress; a god fit for a culture newly liberated from nature, and anxious to see how high it could climb.

In this severe new arrangement the woman’s role could only shrivel and harden. Her cyclical rhythms, the interiority of her sexuality, the porousness of her boundaries: these now presented as obstacles to the linear thrust of civilization. She would have to be carefully circumscribed, a task that Christianity took up readily. Its original apologist St. Paul made the pecking order absolutely clear, declaring that “the head of every man is Christ; and the head of the woman is the man.” His early heirs like Augustine elaborated on how the feminine influence, ruled more by “the promptings of the inferior flesh than by the superior reason,” threatened constantly to drag us down into savagery. Not only would women need to be contained, but men would need to be carefully protected from them, by vows of celibacy if necessary.

Augustine saw the helpmeet Eve and all her daughters as existing “specifically for the production of children.” But by the nineteenth century, as reason consolidated its global hegemony, even fertility per se became dispensable. More important than simply populating the earth, than beating back the unknown, was the job of raising strong new reasoners to maintain and manage it. With the new cult of motherhood, the severing of women from their bodies and the dismantling of their autonomy were all but complete.

Even in the Middle Ages, the Christian fear of the feminine had betrayed its persistent power: female lust was understood as an active, formidable force, and the female genitals, as we’ve seen, were a familiar and compelling icon. Supporting this were the prevailing theories of physiology, still dominated by the Roman doctor Galen, who held that sex was a meeting of active equals and that the female orgasm was a necessary part of conception.2 That had all gone out the window by the time of the Victorians, whose gynecologists could blithely opine that “the majority of women (happily for them) are not very much troubled by sexual feelings of any kind.” As for the minority, they could be treated for hysteria, and medicalized right back into their place. Meanwhile the public images of women that the culture generated were increasingly soft, passive, hairless, sexless. From its position at the forefront of the sacred gallery of Chauvet, the vulva, that antirational emblem of everything damp and labile and concealed, had undergone a miraculous vanishing act.

Vanished, but far from forgotten. Because here are the truths whispered by the Song of Songs, by the visions of monks, by the Ode to Joy and at last by “Be My Baby”: when longing has most passionately bubbled up from the human psyche, it’s been hopelessly entangled with sex. And: in the dreams of the longing subject, prisoner of the patriarchy, the feminine has been irrepressibly central. Our longing, in other words, is a long-suppressed plea for the restoration of the missing pieces of the divine. And could it be that longing itself, in its highest form, is one of those pieces? We’ve seen how the mystics’ aching state of grace degenerated into our own vague nostalgia. We struggle to find words for our feelings because the system we live in has worked to suppress them, to render them senseless. Why does it see them as a threat? Not just because we often happen to long for its antagonists, the fallen angels, but because the mere act of longing is devilishly subversive in itself. To dwell in longing is to affirm that there is a horizon that cannot be reached, a territory that cannot be conquered, an Other that cannot be reduced to a symbol. It is to assert one’s smallness, one’s vulnerability, the openness of one’s pores. It is to find an ecstasy in these limits that flies in the face of certain things our culture holds sacred.

–

1 Nietzsche, who came around to seeing Wagner’s art as “sick” and “decadent,” would have had things to say about this. For him part of the composer’s sin was abandoning the strong, organic rhythms and harmonic journeys of old, and by implication, abandoning the body. Confronted with the new music, he complained, “one walks into the sea, gradually loses one’s secure footing, and finally surrenders oneself to the elements without reservation: one must swim. In older music, what one had to do in the dainty, or solemn, or fiery back and forth, quicker and slower, was something quite different, namely, to dance.”

2 I don’t want to glamorize medieval sex politics. The Galenic model was a double-edged sword for women – for example, the notion that conception implied consent offered an all-too-convenient defense for rapists.