I’ve now told you everything I know about how “Be My Baby” came to be. And yet we’ve only been dancing around the edges of the song itself. We’re no closer, really, to understanding what it was that drove Brian Wilson to the side of the road in shock. Or what it was that put it on a near-divine pedestal for many other greats – what led Neil Young to say it was “in his soul,” or Keith Richards to say it “touched his heart.” Or what it was that so captivated Ronnie Spector herself that, even after the Ronettes’ aftermath took her to hell and back and she’d performed it a million times, she would still report in her old age that the song “just does something to my whole body.” Or, for that matter, what it is that causes in me such a strange stirring.

There have been hints. The rhythmic tension masterfully managed and released by Hal Blaine. The knockout Bardot blend of purity and sex bottled in Ronnie’s voice. The sheer overwhelm of the fully fortified Wall of Sound coming at your ears. But while these things make it a great record, they don’t make it a unique one.

A lot of very smart ink has been spilled over “Be My Baby,” and much of it bears repeating. For many critics its position in history, and the authority and directness of its female voice, make it a feminist proclamation without parallel in pop music. “Ronnie sings as if the honor and bravery in speaking up were all,” writes Stephanie Zacharek. “In fact, she sings as if she knows that the boy’s returning her love is secondary to her own assuredness.” It’s the breathtaking sound of a girl stepping off into womanhood – a girl whose mother had literally just given her the blessing to do so! – and, simultaneously, the sound of a generation of women stepping out from the shadows.

“Be My Baby” does work well as a passionate closing statement for the girl-group era. In giving unprecedented commercial voice to America’s voiceless, the girl groups had supplied crucial reinforcement to the civil rights and women’s rights movements, spreading over the airwaves “both a moral authority and a spirited hope for the future.” These are the words of Susan Douglas, who believes in pop music’s capacity to inspire “a kind of euphoria that convinces us that we can transcend the shackles of conventional life…when tens of millions of young girls started feeling, at the same time, that they, as a generation, would not be trapped, there was planted the tiniest seed of a social movement.”

For others the real revolution here is all about sex, and about the song’s subversion of its pervasive masculine forms of representation. Maggie Haselswerdt notes that rock is largely defined by its more phallic, aggressive expressions – its “driving beat, piercing guitar lines, pounding keyboards and expansive, stage-dominating gestures” – but that many of the very sexiest songs get their power by appropriating the feminine:

In this context, The Song is “Be My Baby”…Phil Spector and the Ronettes weave a gauzy curtain around the sexual impulse, diffusing and romanticizing it, blurring the focus with walls of vibrating sound, highlighting the drama of the encounter with a series of minute yet heart-stopping pauses. “So c’mon and be…be my little baby” leads to the almost unbearably intense moment when Ronnie’s famous “Wa-oh-oh-oh” is punctured by a reprise of the devastating opening beat. That’s as close to what I mean by melting as mere vinyl can come.

Tim Riley echoes much of the above, extolling “Be My Baby” as an “otherworldly visitation of sexual rapture.” He also points out that it can’t help but bear the stamp of two titanic forces wrestling for control. Spector’s mad drive for total mastery of the elements, and the irresistible authority of the liberated female voice, set up an epic drama that we listeners feel in our bones. And within it, complicating and elevating our response, is the all-too-human yearning of the antagonist – for the sound of “Be My Baby” is not only that of “a woman’s voice glorified beyond all reason, but the sound of a man’s response to that romantic fantasy and his total, unfiltered adoration of how much power women really wield over men.” In other words: if the Bobbettes represented an early skirmish between the threatened male ego and its restless female subordinate, with the Ronettes we reach the full Shakespearean climax of the war.

All this is true and right. But is this all? I suspect most of us who love this song would resist reducing it to gender politics or sex, as powerful as these themes are. We might protest, too, that there’s something that makes it timeless – that thoroughly transcends even Spector’s other work with the Ronettes, and captures our hearts even in total ignorance of its context or its circumstances. What is it doing to us? How does it do it?

Dredge the YouTube comments on a “Be My Baby” video and you’ll find some clues. The word “timeless,” indeed, is everywhere. Now and then there’s a reaction of surprise and confusion from a listener of a younger generation. This song is making me nostalgic for a time I didn’t even live in. Or: Just got tears in my eyes and don’t even know why. Alongside these are a few old-timers, chiming in with awakened memories of romances long lost or miraculously preserved. One comment I found was from a young woman who was moved to tears by looking forward to being an old person capable of such reminiscence. There’s a strong time-travel magic afoot.

Love and longing, love of longing, longing for love – these are what it elicits in us, most deeply. That’s no great discovery, of course, given that these are what it’s explicitly about. Its sound is a direct recipe for nostalgia, too: the harmonic quaintness to the modern ear, combined with the grandiose orchestration (and topped off by Spector’s elysian echo), practically oblige us to pine for a romanticized yesteryear. Yet that’s true, to a greater or lesser degree, of any number of songs from the same era. If “Be My Baby” says something to us that these songs do not, where does it say it?

A rock song, more than any other work of art, is an invitation to move our bodies. That much we all know. But an invitation doesn’t mean much if it’s not to something, and herein lies rock’s true genius: in the archetypal structures it offers us to escape to and briefly dwell in, structures so fundamental (some would say “primitive”) that they can cut across all boundaries and entrain us en masse. When we answer a song’s invitation we’re in some sense joining the circling dancers around the fire, resynchronizing the tribe and rehearsing together the basic patterns of existence: seeking, finding, rushing, waiting, revelling, sulking, dominating, submitting, or just grooving.

The most obvious ways it does this are rhythmic – starting with the most primitive rock pattern of all, the backbeat that serves as the invitation’s nagging call and response. Boom? Blam. Looped relentlessly and set to a tempo that’s in the sweet spot of human locomotion, it’s an all but irresistible cue to get up and get in line. Once that expectation is there, it can be toyed with in any number of ways. For instance: every other response can be silenced, as we’ve already seen with Hal Blaine’s snare, so that after three beats of waiting we’re chomping at the bit to move.

More subtle but no less potent are the harmonic patterns – the relationships between pitches – that help to entrain us. In rock these are characteristically framed as repeating sequences of two, three, or four chords, mainly of just three types: major, minor, and dominant seventh (the latter being a three-note major chord with an extra note borrowed from the seventh pitch in the minor scale). By the standards of “art music” it’s a comically limited vocabulary and grammar, but it turns out (as with fairy tales) that you can use it to sweep your audience up in a vast array of universally resonant stories. To some extent, of course, that depends on your audience’s familiarity with the elements. But those elements are not arbitrary, and it’s the physical and physiological truths at their root that have allowed rock to conquer the world in record time.

Apocryphally or not, we credit Pythagoras with the first discovery of those truths. String up a tight string and pluck it, and it vibrates at a certain pitch. Pinch it at the exact center and pluck one half, and it sounds almost the same, just higher: we call this an octave, the most fundamental musical interval. Now take your string, divide it at the one-third point – the next simplest ratio – and pluck either end. It’s clearly not the same note now, and yet it sounds good, right, harmonious with the original, because the wave patterns of the two vibrations hardly interfere with each other. This interval between whole and two-thirds is the beginning of all music. It’s known as the perfect fifth, somewhat confusingly: imagine your do-re-mi scale and if do is your original string, then the scale’s fifth note, so, is sounded by the two-thirds string. That we hear these as being in uniquely close relationship is betrayed by the cadences and overtones of our everyday speech, which have been found to cluster around pitches separated by a perfect fifth.

But with close relationship comes codependence. When we’re acclimated to do as our “home” pitch and we then hear so on its own, the latter triggers the reflexive expectation of the former – of returning home. Flesh these two notes out into chords and that felt need for homecoming becomes acute. Imagine playing only the white keys on a piano. The C major scale can be played with these keys, as many of us remember. Start on G – the fifth note of the scale – and the new scale played from there, with the same keys, isn’t quite major. It’s got an F instead of the F sharp that belongs in G major, and if you play a chord using the first, third, fifth, and seventh notes of this new scale, you’ve got the dominant seventh chord we mentioned earlier. Notice that there are two notes in this chord, B and F, that stand in an awkwardly close, dissonant relationship to two notes in our home C major chord, C and E. This makes the expectation of resolution intense. The G dominant seventh chord promises our arrival back at the C major chord, so strongly that this sequence is called the perfect cadence.

So with I (the root note’s major chord) to V7 (the fifth note’s dominant seventh chord) to I, we have our most basic harmonic journey. A safe step away from home, and a scamper right back. To modern listeners this sounds obvious, hokey, square, and is generally relegated to children’s songs or country (see “Achy Breaky Heart”). But even this infantile progression offers multiple possibilities, depending on how the chords are timed and sequenced. Return to the I by the end of the sequence (“How I wonder what [V7] you are [I]”), and the homecoming becomes the point of the journey. End the sequence on the fifth instead (“Up above the world [I] so high [V7]”), and the journey itself becomes the focus, however assured we are of the eventual return. If you can feel how those two progressions pack a different emotional punch, then you’ve already begun peeling the veil from pop’s harmonic secrets.

Stretch this basic principle just a bit further, postpone homecoming by one or more extra steps, and you’ve got a key piece of musical trickery known as the circle of fifths. Start on the I chord again, but now move up to the second step instead of the fifth. In the key of C that means you’re starting on D, and the D chord with all white keys happens to be a minor chord – so we’ll mark it with the customary lowercase for minor, as the ii chord.1 Now, count notes and you’ll notice that D is the fifth of G, just as G is the fifth of C. So moving from our D minor chord to our G dominant-seventh feels kind of right, like a temporary resolution, like making it to third base, and coming home from there to C fulfills the promise. ii-V7-I is another extremely common element of rock progressions, and these sorts of circling maneuvers are even more ubiquitous and multifarious in jazz, where they’re known as turnarounds.

And now we’ve gotten somewhere, because I-ii-V7 happens to be the progression underlying the verse of “Be My Baby”:2

The night we met I knew I needed you so

I—————-I—————ii————-V7—————

C—————C—————Dm–——–G7—————

It’s nothing fancy, even for 1963 – you’ll find this sequence in dozens of songs from this period – but it signals a couple of things. One is that we’re going somewhere. The other, indicated by the fact that we’ve already got major, minor, and dominant seventh chords on the table, is that the journey might not be totally emotionally simple. And there’s one little touch that cleverly ratchets up the tension. Although the guitars and keyboards move from ii to V7 in the fourth measure, the bass remains on the second (D) until the end of the sequence. It’s a subtle thing, subtle enough that I didn’t notice it for a good while, but it suggests a coy reluctance to resolve and heightens our anticipation of the next section.

As we begin our approach to the chorus, we suddenly find ourselves on more foreign ground. The next chord, E dominant seventh – Oh won’t you say you love me – is unexpected enough to give us a jolt. That’s because for the first time we’re hearing a note, G-sharp (the third in the E scale), that’s not in our “home” key at all. How does this fit in?

When we left the circle of fifths we were on the second chord, which is the fifth of the fifth. Give that circle another turn and you’ll get to the sixth chord (the fifth of the fifth of the fifth), and then in one more turn to the third, which in our case happens to be E. So it could be that we’re setting off on a giant, four-step turnaround back to the root – and in fact that’s exactly what happens, as we move from E to A for two measures (I’ll make you so proud of me), then our old friend D for two more (We’ll make them turn their heads), and finally to G (Every place we go). But it’s a turnaround with a bit of a twist. If we were playing it safe and sticking to the white-key versions of these chords, we’d be looking at E minor, A minor, and D minor. Instead the song opts for the dominant seventh versions of all three chords, which throws multiple black keys into the mix.3 The effect is to make this section both more confident and more exotic – sexier – while still leading us methodically towards our destination.

Here again there’s an extra touch that heightens the tension. At the very top of the melodic line sung by Ronnie sits an F note, reached twice (“say you love me” and “so proud of me”). While this note fits in our home C scale, it has no business at all in either of the chords featured over this stretch: it’s a half-step above the root note of the E chord, and a half-step above the fifth note of the A chord. Featuring this note so prominently as the band plays the latter chords creates an exquisite dissonance, leaving our ears begging for release back to harmonic safety. It also adds another dash of exoticism, since one place where you do find an F in an E scale is in the Phrygian mode famously employed by flamenco music. An intentional wink to the “girl from Spanish Harlem”? Probably not, but the fit is natural: the way Ronnie revels in squeezing out these notes is almost too much to bear.

Once we get to the two measures of G7 leading into the chorus, we know we’re being steered back to C and we’re enjoying the ride. The melody begins to climb (Every place we go, so won’t you…), and midway through Blaine breaks into a delicious drum fill; climax is imminent. We’re about to arrive at what the song has been promising, and withholding, all along. Fittingly, it’s on the word please that we make it at last. And…where are we?

The first time I grasped what the chord progression was in the “Be My Baby” chorus, I had to laugh. A measure of C, a measure of A minor, a measure of F, and a measure of G. It’s not only that there’s nothing at all harmonically unusual here; it’s that these four chords are predictable to the point of cliche. I-vi-IV-V is so peculiar to music of the 1950s and early ‘60s, and so inescapable there, that the pattern has been dubbed the “50s progression” or “doo-wop progression” – or, more derisively, the “ice cream changes,” in mocking tribute to its prominence in the soda-shop jukebox canon. It’s the very first progression that countless piano students learn, as the left-hand part of the timeworn “Heart and Soul.” How could something this vanilla, this old-fashioned, undergird the crowning moment of a song supposedly communicating feminist revolution, let alone carnal triumph?

This is “Be My Baby”’s greatest single trick: making the old ice cream changes sound so damn good. Good to the point of rocking, even. To understand how, we’ve got to take that progression apart and see what makes it tick. It won’t hurt to trace where it came from.

The tune of “Heart and Soul,” penned by Hoagy Carmichael in 1938, is prehistoric by rock standards. But the first appearance of the ice cream changes – at least, of their essential components for our purposes – is more ancient still.4 The date is 1933, when the musical-theater titans Rodgers and Hart were in their “selling out in L.A.” phase. They’d been tasked by MGM with writing a song for a film called Hollywood Party, which turned out to be basically an awkward pile of cameos and in-jokes that tanked at the box office after cutting a bunch of scenes and numbers, including this one. But the song wouldn’t die, and to Hart’s mounting exasperation he wound up fully rewriting the lyrics three times over a period of years at the studio’s whim. (At one point it had the working title “The Bad in Every Man.”) Eventually, and against the composers’ better judgment, it emerged as a baldly commercial single with a happily-ever-after plot – and, under the title “Blue Moon,” went on to be one of the most recorded songs of the twentieth century.

In assessing the meaning of the progression, “Blue Moon” in its canonical version is something of a red herring. More revealing is the song’s original, scrapped incarnation. One of the many proposed characters for Hollywood Party was an innocent young stenographer desperate to be a movie star, and the idea was to give her a musical plea to God to fulfill her dreams. Oh Lord, if you’re not busy up there / I ask for help with a prayer… The joke was that the ingenue was to be played by Jean Harlow, the original Blonde Bombshell, who was by then well into superstardom and the most potent sex symbol of the day.

There’s longing, then, somehow straddling the carnal and the spiritual. That Richard Rodgers, one of the most practiced tunesmiths of all time, would have chosen these four chords to represent it is surely not arbitrary. The sequence begins by moving from the key’s root to its relative minor (C major to A minor, say): its downcast twin that shares all the notes of its scale, and two out of three notes of its basic chord. Thus this first move is a transformation of our “home state” into a state of despair, of melancholy. How could our prayer ever be answered? How could our love ever be returned?

The next change in the Changes is the most ambiguous. In its original form it goes from vi to ii, D minor according to our mapping, thus merging into a proper circle-of-fifths turnaround. But among the countless “Blue Moon” covers that started proliferating soon after its publication, most of the ones since the dawn of the rock era use a IV chord (F major) instead. The two chords ii and IV are exceptionally close cousins, sharing two notes and often doing the same job: a job labeled subdominant or predominant, which is all about setting up the dominant, or fifth, chord to do its work. While the Juilliard-trained Rodgers may have preferred the more classical move, in the long run the youthful energy and blues connotations of the IV (more on that later) won out.

Either way, the predominant-dominant sequence in the changes’ back half conveys a growing hope (with the shift back to major and the rising pitch), along with a mounting tension as we approach release. But because we don’t return to the root within the frame of the progression – whether that’s two bars, as in its quick-moving form in “Heart and Soul” or “Blue Moon,” or stretched out to eight as in “Be My Baby” – we feel the journey as unresolved. So then: the establishment of an ordinary, everyman baseline (I); a lapse into melancholy (vi); an unfulfillable, but unquenchable, hope (IV-V); and repeat, like Sisyphus. What simpler way to represent young longing through music?

“Blue Moon” cropped up on the charts several times in the ‘40s and ‘50s; among its interpreters was Billie Holiday, whose fluttery vibrato and playful stretching and slowing of notes were obvious influences on Ronnie Spector. But the ice cream changes wouldn’t find their real home until the dawn of the rock era, when we find them repurposed for the 1954 smash “Earth Angel” by the Penguins. These were a quartet of L.A. high schoolers who did their recording in an actual garage, and the authenticity of their longing – I hope and I pray, that someday / I’ll be the vision of your hap, happiness – worked like Pavlov’s bell on the new, hungry teenage market. (You’ll find original 45s of the single in multiple colors, as the tsunami of demand caused the label to literally run out of paper.) “Earth Angel” went on to become one of the key touchstones of doo-wop, “the grandaddy of them all” in the words of Alan Freed, and the tune that Ellie Greenwich claimed gave her the first taste of heaven.

A further innovation came with 1955’s “Unchained Melody,” whose title was less pretentious than it sounds, as it was written for the prison-break movie Unchained. Leaning in to the melodrama inherent in the progression, the song slowed it down to one chord per measure and piled rapturous strings on top of its more sophisticated lyrics; the latter kept the spiritual flavor that seemed somehow baked into the ice cream changes (God speed your love to me), and added intimations of an ambiguous, oceanic bliss (Lonely rivers flow to the sea). Proof that this was an meaningful breakthrough came when no fewer than four different artists took “Unchained Melody” to the top twenty in its first year of existence (and that doesn’t include its signature recording, which will figure into the story later, naturally enough).

By the time Ronnie’s crush Frankie Lymon borrowed them for “Why Do Fools Fall in Love,” the Changes had been firmly cemented as the go-to template for the doo-wop love song. Dip into any Billboard chart from the last years of the 50s and first years of the 60s, and you’ll quickly lose count of the songs that feature it. Plenty of songwriters used them straight-up, while others took liberties with the progression that helped illuminate its meaning. In 1961’s “Stand by Me” – recorded with Phil Spector in the booth, remember – Ben E. King expresses not longing for an unattainable object, but ongoing need for the partner he’s already got. No coincidence that the progression is adapted accordingly, hurrying through the IV-V section to a satisfied landing on I before the end of the frame. (Even here the spiritual aspect is inescapable, as King took inspiration from the gospel tune “Stand by Me Father.”) Like many songs whose form and content align so sweetly, “Stand by Me” transcended its time and became the fourth-most performed song of the century.

But liberties notwithstanding, the basic blueprint for a Changes song was settled by then. If you had to write a parody of a fifties song, you’d start with something like “Earth Angel” or “In the Still of the Nite”: a slow-to-mid-tempo, swaying 6/8 beat, with gentle piano triplets and silky shoo-bee-doos. It’s the sound of a sweet, innocent dream, or at most a very chaste slow dance. If you moved your body to such a sound, you didn’t move it much.

The progression could be made harder or faster, of course, but generally something would be done to dilute its seriousness. Examples of this flourished in the years leading up to ‘63 as pop songwriting became more self-conscious. Childish handclaps (“Lollipop”), nonsense words (“Who Put the Bomp”), picture-book premises (“Please Mr. Postman”), cheeky thematic inversions (“Runaround Sue”), seasonal novelty (“Monster Mash”) – all served to put the Changes in their corner, cautioning the Baby Boomers that while that sound may have defined their adolescence, that’s where it would stay. Even “Blue Moon,” when it finally reached number one in the hands of the Marcels in ‘61, was garnished with such new sentiments as “Ba-dang-a-dang-dang / Ba-ding-a-dong-ding,” no doubt causing several turns in the grave for Lorenz Hart.

“Be My Baby” breaks all these rules. In its chorus it trades in the halting baion for a straight-up, driving 4/4 backbeat, unmistakably rock. It positively wallows in the progression, spending two full measures on each chord. Castanets come in out of nowhere, a decadent topping that signals us to quit slow-dancing in the corner and come galloping off on this euphoric feeling, to wherever it might carry us. And while the word “baby” itself may have been an infantilizing choice on the part of Phil Spector, as delivered by Ronnie there’s no doubt it’s the croon of a fully adult lover.

It does something else new, too. Listen to the backing vocals. It’s unusual enough that they take precedence in the chorus, making their statement (Be my, be my baby) before Ronnie’s (Be my little baby), and it turns out to be only them who actually speak the titular words. So it’s up to them to set the tone, and they do so by beginning on a C – and then quickly descending to, and repeatedly lingering on, the B just a half-step below. “Be my, be my ba-by / My one and only ba-by.” That B is the most prominently featured note in the whole section, and that’s remarkable, since it’s the most dissonant pitch, the most desperate to resolve, in the whole home scale of C major. Holding it through the transition to A minor, and then especially to F major – a scale in which it doesn’t even appear – turns that mischievous initial slip into a stubborn straining against physical bonds. Whether this was Ellie Greenwich’s brainchild or Jack Nitzsche’s or someone else’s, it’s an inspired move that forces us to face the full ache of yearning.

“Be My Baby” brazenly flashes the ice cream changes as the central jewel in a rock setting. It forces us to take them seriously. And in so doing it reveals their truth, a truth that for whatever reason music had tried to obscure for decades. The power of that chorus, the power that instantly seized Brian Wilson by the spine, goes way beyond puppy love to insist on longing as a core feature of mature human experience; as in some way an end in itself; as an ecstatic state worth pursuing for its own sake.

The release of the single coincided, almost to the day, with the arrival at adulthood of the very first children born after the World War. Now that the ice cream generation was growing up, you might expect this revelation of the Ronettes’ to be taken up by countless imitators. Who wouldn’t want to reproduce a sound that good?

What happens instead is something very different. According to its folkloric telling, it all hinges on the Kennedy assassination. In a synchronicity that only flatters the myth, the Ronettes themselves are actually present for that momentous event. Out on tour with Dick Clark’s “Caravan of Stars” and booked for Dallas on November 22nd, they’ve ridden the bus from Wichita the night before and stayed up all night in hopes of catching the presidential motorcade. Their hotel is only a few blocks from Dealey Plaza, and some members of the Caravan, standing on the steps outside, hear the gunshots live. Ronnie, Estelle, and Nedra catch the report on TV instead, and are milling around the lobby in shock when confirmation comes that the president is dead. The show is canceled, as is everything else.

Another canceled thing: Phil Spector’s latest project, which has been scheduled to hit shelves on this very day. It’s his Christmas album, to which he’s devoted himself and his team with such a weird, quixotic drive this fall that they’ve started questioning his sanity. Perhaps it’s just that the vision of himself as Santa Claus suits his megalomania. The record gets the ridiculous title A Christmas Gift for You from Phil Spector, with a self-indulgent recorded message from Phil himself at the end, and with cover art featuring the Ronettes, Crystals and others emerging from wrapped boxes in smiling rows. Roses in his garden, indeed. But in a cruel twist America is suddenly in no mood for cozy nostalgia, and Phil yanks the release. It’ll be years before undeniable classics like Ronnie’s “Sleigh Ride” get their due.

As the story goes, the crushing of America’s spirit that day leaves a vacuum into which the British Invasion gladly rushes. “I Want to Hold Your Hand” comes bopping across the pond the day after Christmas, and by spring the boys from Liverpool have rung in a new cultural season and driven a stake into the doo-wop and girl-group sounds. The allegation is ironic, given how deeply they’ve drunk from that American musical well, and not entirely fair, given that signs of change have been swirling on both sides of the Atlantic for some time. But it’s an unavoidable fact that the Top 40 sounds very, very different a year after Ronnie’s reign.

To hear how, start with “Baby, I Need Your Loving” by the Four Tops. Released in July 1964, it would become Motown’s first certified platinum record and one of the most iconic songs of the year. Thematically it’s no departure from earlier songs of soulful longing, though the verbing of “love” gives it a slightly risque adult touch. But the track starts with a chord progression that – while deeply familiar to modern ears – sounds very fresh and different in the early sixties. It starts on what we assume to be the I (call it C), and then instead of moving to another chord contained in that root scale, picks one anchored on a black key, B-flat major (bVII, the b denoting a flat). An F, the IV chord, ends the progression as the Tops deliver a soulful wordless refrain.

bVII to IV to I – it’s a turnaround kind of like the circle of fifths, but in fourths instead (since B-flat is the fourth of F). But that greatly understates its difference. Flip it backwards and it does match the circle of fifths (C is the fifth of F, F is the fifth of B-flat) – which means that this progression doesn’t just tweak the old standard, it turns it completely upside down.

There’s a name for this pattern, epitomized by the coda to “Hey Jude” but plentiful in late twentieth-century rock. It’s called a double plagal cadence, a heretofore obscure variant of the plagal IV-I used by a thousand hymns for the specialized function of delivering the final “A-men.” The odd term plagal comes from the Greek for something like oblique, which hints at its harmonic dysfunction: it doesn’t seem to fit in anywhere to the classical program of building and resolving tension.

And in a way, that’s the point. “Baby, I Need Your Loving” is just one of a sudden efflorescence of songs that diminish the ancient role of the fifth and hold up the fourth in its place. It’s an invasion, yes, but to look to Britain for its source is to be fooled; the Beatles and the rest have taken their harmonic inspiration, quite openly in many cases, from the American blues. The centrality of the fourth captures the blues worldview more than any other musical characteristic, and not only in its subversion of establishment expectations. Notice that the one note that the F major scale does not share with C major is B-flat. Change a B – the note featured in the backing vocals in the “Be My Baby” chorus – to a B-flat, relieve that straining pitch of its tense closeness to home, and you’ve changed earnest yearning into jaded resignation. You’ve created cool. And the cool sound of the Four Tops, as revolutionary as it is, so effortlessly foretells the next era in rock that it sounds utterly normal to us today.

If there’s any doubt that this shift is not just aesthetic but political, leave it to resident rock philosopher Frank Zappa to dispel it:

Many compositions that have been accepted as “GREAT ART” through the years reek of these hateful practices. For example, the rule of harmony that says: The second degree of the scale should go to the fifth degree of the scale, which should go to the first degree of the scale…Tin Pan Alley songs and jazz standards thrive on II-V-I. To me, this is a hateful progression. In jazz, they beef it up a little by adding extra partials into the chords to make them more luxurious, but it’s still II-V-I. To me, II-V-I is the essence of bad “white-person music.”

So the familiar old fifth chord has been served notice by the revolutionaries. What else can you do with the fourth? One option is revealed by the next section of “Baby, I Need Your Loving”: you can just step back and forth between I and IV, and that feels good. It feels so good that it becomes the fundamental rock groove, representing movement for its own sake, without the expectation of going anywhere. By 1965 everyone will be I-IV grooving, to songs like the Stones’ “Satisfaction” and Otis Redding’s “Respect” and Wilson Pickett’s “In the Midnight Hour.” The fifth never appears at all in many of these tracks, and in fact never appears in “Baby, I Need Your Loving” – at least, if you assume the I to be the first chord in the song, which is debatable, since the chorus is rooted on B-flat instead. That instability, that refusal to commit to a single home, will be another recurring theme of the music to come.

As for the Beatles, like many of their contemporaries they’re eager to cast off the shackles – of classical form, of repressive postwar morals – and they find in the blues the tools for the job. Suspicious of subliminal influence from the establishment, Lennon and McCartney wear their inability to read music as a badge of honor. But they’re also instinctive harmonic geniuses, and it’s their sophisticated elaborations of the basic blues motifs that lay the groundwork for rock as art. “A Hard Day’s Night” is a great example, from the spring of 1964. The bVII chord that lands on “working…like a dog” says everything about the metamorphosis that’s been occurring since “I Want to Hold Your Hand” just a few months earlier: instead of boyish flirtation we now have the ennui of a working man, and the flattened harmony to go with it. The lads are growing up, and growing up into a society that’s both relishing its new horizons and struggling to find its bearings.

What has happened during that interval? The first quarter of 1964, notably including their first trip to America, will arguably go down as the most pivotal stretch in the Beatles’ entire career. And it starts with a meeting that in hindsight will look like a massive passing of the torch: the meeting between the Fab Four and the Ronettes.

The girls are launching their first overseas tour, with the babyfaced Rolling Stones as their opening act; the lads are prepping for the reverse trip. They cross paths at a party in London, at a posh Mayfair townhouse, in early January. Given what the two acts will often be reduced to in the future – the crowning jewel of the old sound and the messengers of the new, respectively – you might expect there to be some strain. Nothing could be further from the truth. They hit it off like a bunch of kids learning they like the same game – which they are, really (Ringo’s the old man of the lot at 23). The Ronettes’ second single, the derivative but still great “Baby I Love You,” finds its way onto the record player and the girls show the boys some new American dance steps. George and Estelle, the “quiet” ones, discover some instant chemistry. John coaxes Ronnie upstairs to show her the view, and manages to steal a kiss (but nothing more – her heart’s back in L.A.). Later on in the trip there will be awkward double dates chaperoned by Mrs. Bennett, souvenir shopping with John in Carnaby Street, an evening spent running around some house playing some parlor game that no one will remember.

To suggest in these days that the Beatles are somehow already destroying the Ronettes and their world would be incomprehensible. It’s hardly a secret that the boys worship the girl groups. Their first albums are liberally sprinkled with covers of “Please Mr. Postman” and the like. “I Want to Hold Your Hand” may have sounded fresh, but flip the record to its B-side – “This Boy,” which also gets picked for their momentous first Ed Sullivan show – and you’re in 1950s Harlem, triplets, close harmonies, “Blue Moon” chords and all. Remember that songs like Spector’s “He’s a Rebel,” while honoring the basic patterns of pop, have already primed their audience for embracing outsiders – cheeky boys who buck the system, maybe even in moptops, by singing straight from the heart. When the Fab Four conquers America it’s in many ways less a surprise than a consummation.

For John it’s more personal. Later he’ll bewilder interviewers by citing as his favorite song “Angel Baby,” a forgotten, textbook ice-cream-changes ballad from 1960 with a hauntingly raw quality (thanks in part to its delivery by Rosie Hamlin, a 15-year-old Mexican-American, and in part to having been recorded on a two-track in a California farm town). When he meets Ronnie Bennett, he immediately begs her to sing “Be My Baby” in his ear, and half-jokingly “passes out” when she complies. And by the time he attempts his own cover of our song a decade later, it’s slow, anguished, full of asides (Oh, I can’t stand it…it’s too much) that suggest he hears something precious and forever lost.

Recovery of innocence will be a torturous lifelong quest for Lennon, who has his mother taken from him institutionally at age five, and then physically, by a speeding car, at seventeen. To say that this does to him what Kennedy’s death does to America wouldn’t be fair to either – and yet, it’s surely no coincidence that the unmoored sixties pick for their spokesman a figure with a complicated orphan’s tale. Haven’t we all been looking ever since for someone to whisper “be my baby” in our ear?

John’s story has to be followed just a bit further, because no single person has a greater influence on what happens to music from this point forward. There are two more chance encounters during those early days of 1964 that conspire to set his path. One is hearing Bob Dylan for the first time, later in January in Paris, and getting a glimmer of an idea of a whole new set of functions for rock and roll. (The impact is mutual: in an uncanny echo of Brian Wilson’s experience, Dylan is cruising down the Pacific Coast Highway with a friend when “I Want to Hold Your Hand” comes on the radio and he all but jumps through the window. Did you hear that? Oh, man – fuck!)

And in March, Lennon gets asked a question that crystallizes everything. He’s just published his first little book of nonsense verse and Thurberesque sketches, In His Own Write, and a BBC reporter idly wonders: why don’t you put the same literary energy into your lyrics? The answer is that, until just recently, he hasn’t even thought of it. For the Beatles as with most of their peers, the vapidity of pop has been part of the point, and the “writing” that goes into a work like “She Loves You” is not real writing. But that viewpoint won’t be sustainable for long.

Feeding into Lennon’s inner crisis is the dread he’s beginning to feel about the implications of his fame. On the one hand there are the terrifying frenzies of which the Beatles’ fan base has shown themselves capable: when they touch down in America for the first time in February, the sound they interpret as roaring jet engines turns out to be four thousand screaming teenage girls trying to hurl themselves over a retaining wall. On the other hand is the startlingly fierce resistance of the old guard. That’s something from which Lennon, a virtuoso of irreverence, has never shied away, but now the stakes seem so high that he’s questioning his fitness for the task. After the Ed Sullivan appearance, Newsweek retaliates to this cultural assault with withering fire:

Visually they are a nightmare: tight, dandified Edwardian beatnik suits and great pudding-bowls of hair. Musically they are a near disaster, guitars and drums slamming out a merciless beat that does away with secondary rhythms, harmony and melody. Their lyrics (punctuated by nutty shouts of “yeah, yeah, yeah!”) are a catastrophe, a preposterous farrago of Valentine-card romantic sentiments.

The truth is, none of the Beatles fully understand why they’re such a big deal. Maybe nobody does, least of all Newsweek. Much later it’ll be possible to piece together a diagnosis of sorts for what’s causing the squeals of hysteria and the snarls of repudiation. The underlying condition is the massive reservoir of energy that’s built up under the thickened skin of Western civilization, through booming population, surging affluence, unprecedented connectivity, and the effort of the collective body to control it all – and avoid the horrible pathologies of the past – with rigid moral infrastructure. An escape valve was always going to be found, and the Beatles, with their sideways harmony, their flippant presentation, their androgynous hair, show the way by embodying the permission to dissolve structure. For their army of fans freshly recruited into adolescence, the realization that they’re unstoppably numerous and inescapably visible is intoxicating, and the screams are contagious to the point of pandemic.

Most conspicuous and most threatening to authority are the female reactions, but it doesn’t stop there, and it’s not confined to Beatlemania. When the Ronettes do a mini-tour of military bases in Germany, the troops respond with what look to Ronnie like “orgasms on the floor”; at one stop violence breaks out among the crowd of men surging at the closed doors, and the girls have to be whisked off in an armored truck. And while the mania in its initial form might depend on pop idols for activation, new tools are on the way that will allow users to dissolve structure at will. The summer of ‘64 will begin with Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters setting off in their rainbow bus to spread the gospel of psychedelics, and end with the publication of Timothy Leary’s The Psychedelic Experience, which will eventually be quoted by Lennon in Revolver and will help send rock into other dimensions.

But he’s not there yet. First he has to learn how to expose himself in his music. His first effort, spurred by that BBC reporter, takes the shape of an imagined bus trip through Liverpool in verse. Along the way he enumerates the sights and reflects on the losses – the ships, the docks, the trams, emblems of the old order shuttered or neglected since his boyhood – in a way he hopes is reminiscent of Tennyson or Wordsworth. It doesn’t really work, and eventually he tightens it up into a more abstract reflection:

There are places I’ll remember

All my life though some have changed

Some forever, not for better

Some have gone and some remain

All these places have their moments

With lovers and friends I still can recall

Some are dead and some are living

In my life I’ve loved them all

But of all these friends and lovers

There is no one compares with you

And these memories lose their meaning

When I think of love as something new

“In My Life” won’t come out till 1965’s watershed Rubber Soul album, but even then it will be something very different from what Beatles fans are used to hearing. The mentions of the dead – which by implication includes John’s mother as well as his effective big brother, the “fifth Beatle” Stuart Sutcliffe, felled by an aneurysm – are startling enough. But the enigmatic allusions to things that have changed “forever, not for better” signal that rock’s attitude henceforth will in large part be one of disillusionment. Though it’s superficially a love song, it’s hard to listen to it and not conclude that superficial love songs are among the things that have now “lost their meaning.”

“In My Life” will only grow in stature, eventually to be crowned in at least one survey as the greatest song of all time. Its lyrics will get the bulk of the attention. But what plants it in direct, fascinating relation to “Be My Baby” is its music, and in particular the novel chord progression Lennon devises for its verses. Let’s look (adapting to the key of C as before):

There are places I’ll remember

C———G——Am——-(C7/Bb)——

I———-V——vi———(I7/bVII)—-

All my life though some have changed

F—(Fm)—-C————————————

IV-(iv)——-I————————————

There are some characteristically Beatlish passing chords thrown in, indicated in parentheses, which add black keys to the palette and help paint a melancholy tone. But focus on the four-chord backbone, I-V-vi-IV. It’s the same four chords as the ice cream changes – just with the V taken from the end and inserted in the middle! What does this simple rearrangement do to our familiar journey of longing?

One thing it does is move the lone minor chord from a transitional role to a position of more centrality, leading the second half of the sequence, so that when the preceding fifth “resolves” it’s not to a safe home but to a place of sadness. Then at the end of the journey, when you’re expecting to be ferried home by the fifth, the plagal (oblique) move through the fourth instead makes the return feel somehow hollow: less of a release than a resignation.

In other words: the “In My Life” changes do convey longing, of a sort, but in a way that makes it clear that its object is irrecoverable.

Do you feel it? Grief, resignation: these are feelings that pop music has had little need to articulate, to this point in history. Accordingly, for such a basic pattern, these changes show an almost uncanny lack of precedent. But there is a much beloved traditional song, also about loss and memory, whose thematic and harmonic similarities are such that it’s hard to believe they didn’t have some influence, some indirect, unconscious bearing, on the reflective Lennon. We sing it every year to bid farewell to the past, and it moves us in ways it couldn’t if the music didn’t help tell the story:

Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind?

I———————-V—————–vi——————-IV—————-

And there is one other precedent, the single pop song I have managed to find that uses the “Auld Lang Syne” changes before 1965. It’s a song the Beatles have actually covered, live at the BBC in July ‘63, so it’s an obvious prime suspect when it comes to tracing influence. Maybe it won’t shock you that it’s also a song that has already figured into this story in a very significant way.

It’s “To Know Him Is to Love Him,” penned by Phil Spector. Another love song, on the surface, by a young man whose pursuit of love is eternally frustrated by trauma. Another song haunted by a parent’s untimely death. Another song that moved its listeners in surprising ways they couldn’t fully explain – but would soon become deeply familiar with.

If this were a one-off phenomenon, it would be an intriguing curiosity that we could set aside. But this harmonic journey turns out to be something rock is drawn to again and again. In combination with the ice cream changes, which it drives virtually to extinction, it tells the story of the culture better than any other musical elements could. At first it surfaces only occasionally, but dramatically, as in McCartney’s iconic 1970 prayer to his own dead mother:

When I find myself in times of trouble

Mother Mary comes to me

Speaking words of wisdom, let it be

And in my hour of darkness

She is standing right in front of me

Speaking words of wisdom, let it be

Or Bob Marley’s iconic 1974 remembrance of his painful, beautiful Trenchtown youth:

Good friends we have, oh, good friends we’ve lost

Along the way

In this great future, you can’t forget your past

So dry your tears, I say

No, woman, no cry

Or the weary Stones’ iconic 1978 relinquishment of love’s delusions:

I’ll never be your beast of burden

I’ve walked for miles, my feet are hurting

All I want for you to make love to me

Or Sting’s iconic 1978 confession of existential solitude amidst the crowd:

Now no one’s knocked upon my door

For a thousand years or more

All made up and nowhere to go

Welcome to this one man show…

So lonely

Or Bono’s iconic 1987 submission to the agonizing compromises of modern (romantic or spiritual) love:

My hands are tied, my body bruised, she got me with

Nothing to win and nothing left to lose…

I can’t live with or without you

In the nineties these grapplings with rock’s most adult themes will go from occasional to de rigueur in certain subgenres, to the point that I-V-vi-IV (and its even more melancholy twin, vi-IV-I-V) briefly earn the unfortunate nickname “sensitive female progression.” Songs like Jewel’s “Hands,” Sarah McLachlan’s “Building a Mystery,” Natalie Imbruglia’s “Torn,” and Alanis Morissette’s “Head Over Feet” use these changes to conjure up love, faith, or empowerment, or the impossibility thereof, against a dark implicit backdrop of oppression or alienation. Most tellingly Joan Osborne’s “One of Us” brings an ambiguous fallen God into the picture:

What if God was one of us?

Just a slob like one of us…

Just tryin’ to make his way home

Back up to heaven all alone

Nobody calling on the phone

Except for the Pope maybe in Rome

And by the turn of the millennium or shortly thereafter, nicknames will be moot as the progression will have completely escaped its “adult” box and become the default template for pop songs with any semblance of sensitivity (even if it’s just sensitivity to the nuances of fellatio, as in Flo Rida’s “Whistle” which will ride these golden changes to the very top of the charts). As they complete their conquest by seeping down into the base matrix of pop, perhaps the greatest testament to these chords’ narrative resonance will be finding their theme refracted through the everyday preoccupations of teenagers. For example, in Avril Lavigne’s precociously weary plea for authenticity (“Complicated,” a #2 hit in 2002)5:

Why’d you have to go and make things so complicated?

I see the way you’re acting like you’re somebody else

Gets me frustrated…

Chill out, whatcha yelling for?

Lay back, it’s all been done before

And if you could only let it be

You will see

Let it be. Those words, echoed across a span of three decades by artists and in contexts with seemingly nothing in common – but set up by the same four chords. A coincidence? Or do those words and those chords together articulate some kind of consistent philosophy for a new age?

The thread is easy to lose, in part because it manifests so differently: as the heroic optimism of Paul’s There is still a chance that they will see (see also Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’”- same chords); or as the cynical demand for momentary pleasure issued by Mick’s All I want is for you to make love to me; or as Bono’s anguished ambivalence. But the basis of all of these, the basis in some sense of all rock after 1963, is the same message. Be cool, it says. Spiritually, romantically, socially: be cool, lay back, it’s all been done. Innocence won’t be regained, the gods will not return, and all we have is each other – so while there is sweetness in the rhythms of life, it’s crucial to accept that trying, searching, longing in the old ways is futile. And it’s all right there in the changes. We start from home (I); we try to fly (V); we reach only a false heaven (vi); we fall backwards to earth, fruitlessly but gracefully (IV). For prophets Lennon and Spector, who discovered all too literally that parents will forsake you and mountains will tumble to the sea, this new pattern of desire came as second nature.

None of this is their fault, or anyone’s. It’s the inevitable result of the postwar generation claiming their Promethean birthrights – freedom from the gods, and unfettered access to each other – and inheriting the technologies that at last enable their realization. When they finally win the ability to do whatever they want, it comes with the haunting feeling of expulsion from some hidden Eden. And despite their best efforts to regain that higher plane with the help of hallucinogens and free love, by the end of the sixties there’s a spreading suspicion that there’s nothing at the end of that tunnel. “The dream is over,” says Lennon in 1970’s anthem of disbelief “God,” and it’s not only he and Spector who are left disillusioned by the string of casualties and broken promises the decade has left in its wake.

And what of the ice cream changes? By the end of the sixties they sound antediluvian – endearingly naive at best, sometimes mortifyingly so, like coming upon your first prepubescent love poem. From “serious” rock they all but disappear, reserved for self-conscious nostalgia (“Crocodile Rock”) or irony (“Happiness Is a Warm Gun”). On the rare occasions they’re used in earnest in the eighties and nineties (“Total Eclipse of the Heart,” “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now,” “I Will Always Love You,” “I’ll Make Love to You”), it tends to be in the service of extravagant melodrama that elicits both commercial success and rampant mockery. Examples from more recent years are more often than not blatantly and opportunistically “retro” (see Charlie Puth singing “Let’s Marvin Gaye and get it on”) as the culture cannibalizes itself with mounting gusto.

On rare occasion in the later twentieth century an artist does achieve something great and new with the progression – but almost invariably by adding a dark twist. The Police’s “Every Breath You Take” takes the guise of a sweet old-fashioned love song, with I-vi-IV-V over the verse, till it lands back on vi instead of I (in what’s classically known as a deceptive cadence) with the decidedly minor-key words “I’ll be watching you.” Crowded House’s “Don’t Dream It’s Over” toys with the changes throughout: the verse starts with I-vi-IV but veers to a dissonant major III over the last bar, while the chorus preserves the original sequence but decenters it so that it ends, deflatingly, on the vi. Fitting contortions for a song nominally about hope but featuring lines as bleak as “There’s a battle ahead, many battles are lost” and “In the paper today, tales of war and of waste / But you turn right over to the TV page.”

And then there’s John Lennon, straining towards innocence till the end. “Woman,” one of the last songs he writes and the first single released after his murder, features a straight-up “Blue Moon” progression over its chorus. Wordless the first two times around (Ooooh, well well…), then with the simple refrain I love you, now and forever over the fadeout, its archaic earnestness is almost too much for the jaundiced modern ear to bear. It’s the emphatic childlike Yes in response to Ronnie’s command on behalf of the divine feminine to be my baby, her baby, our baby – issued in the same days that Lennon is famously photographed naked, fetal, clinging to Yoko. With his passing, one wonders if there is anyone left on Earth who can articulate such a thing.

Amidst the roughening seas of the mid-sixties, Phil Spector rides his wave as long as he can. From the Ronettes he milks a series of hit singles, continuing the “Be My Baby” conversation with such inspired titles as “Baby I Love You,” “Do I Love You,” and “You Baby,” though none have quite the success or the staying power of their first. Meanwhile he takes on a new project, a young blue-eyed soul duo who’d landed a gig as the opening act for the Beatles on their first tour of the States. By slowing the Righteous Brothers down to a swoon and enthroning them atop the Wall of Sound, he produces two records of epic proportions that forever cement his reputation: one a new Brill ballad, “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” and the other an authoritative take on “Unchained Melody.” The latter in particular, presenting the ice cream changes in their fully deified form, already strikes a faintly anachronistic note on its release in 1965. In later years it will so powerfully evoke longing – for a hopelessly distant object, from a hopelessly distant time – that its defining role will be in a scene featuring two lovers separated by death itself (1990’s Ghost, with our old friend Patrick Swayze).

But Phil’s still not convinced that he’s fulfilled his destiny, and it’s with a hint of desperation that he starts work on what will be his true climactic statement. For his script he picks yet another expression of pure love cosigned by Barry and Greenwich, this one explicitly tracing the thread between a girl’s attachment to ragdolls and puppies and the “stronger…deeper…higher” commitment of a mature woman. But for his protagonist, for what he has in mind, someone like Ronnie won’t do. Instead he digs up 26-year-old Anna Mae Bullock, a.k.a. Tina Turner, whose thrillingly raw voice (“like screaming dirt” in the words of an early admirer) has been honed far from New York and L.A. on the “Chitlin Circuit” of her native South. Convinced he has the ingredients of his magnum opus, he welcomes everyone he knows to sit in on the sessions, from Mick Jagger to Dennis Hopper to a meek, wordless Brian Wilson.

For “River Deep – Mountain High” Turner lays it all on the table, clinching the final take with the lights out, shirt peeled off, drenched in sweat. The record sounds desperate, thanks not only to the ferocious vocal but to the rushing tempo and the instruments scrambling to pile on top of each other before the 3:40 is up. It’s gigantic, it’s gutting, it’s “like God hit the world and the world hit back,” in the words of Jerry Garcia – and it’s a flop. Though it catches on in the UK, it barely cracks the charts in the States, where its blend of earthy, sensual fervor and baroque orchestration seems not to compute.

The fear of rejection has been festering inside Spector for most of his life, and when it’s realized in this way the result is catastrophic. He tells colleagues at Philles he’s going to close up the shop for good. He makes an abortive effort to get into films, then effectively shuts himself up in his rambling house in Beverly Hills, guzzling Manischewitz wine and obsessively watching Citizen Kane. When he emerges it’s in an increasingly grotesque form, with wigs and accents and diamond-shaped spectacles and a phalanx of bodyguards, picking fights just to vicariously enjoy their brutality.

The parallel with Wilson is eerie. Both men are hurled off at the same time by the runaway train of the sixties (their final masterpieces, “River Deep” and Pet Sounds, appearing within days of each other), and both men close out the decade by retreating, pupating, morphing into caricatures of themselves. This takes them in superficially opposite directions, Wilson becoming a fat, addled man-child, Spector a violent, cynical little goblin. But the wounds they nurse underneath are deeply connected. Both were nurtured and then repudiated by their fathers, only to have their entire culture reenact that ultimate treachery – anointing them as bearers of its greatest treasures, then informing them that those treasures were, to quote Lennon, only memories that lost their meaning.

Phil’s few public statements in the years after “River Deep” strike a bitter tone:

Everybody’s a helluva lot hipper today, I’ll tell you that. There’s 13-year-old whores walkin’ the streets now. It wouldn’t have happened as much five years ago. Not 13-year-old drug addicts. It’s a lot different today. I tell you the whole world is a drop-out. I mean, everybody’s a fuck-off. Everybody’s mini-skirted, everybody’s hip, everybody reads all the books. How in the hell you gonna overcome all that?

He must grasp on some level that the producer playing God is an offense to the new spirit of the time, with its insistence on individual expression, on liberating the tools of the system. But he can’t accept another way, so he settles on drugs as a scapegoat for his public’s unaccountable betrayal. “I know I can make hit records,” he says defensively, as his decade of triumph approaches its dismal end. “I’m apprehensive about certain people who don’t have any standards but drug standards, really. If they’re loaded at one time, my record will sound great; if they’re not loaded, it may sound bad.”

Turning his back on the Wall of Sound, he focuses his tremendous drive for control instead on the nearest human target: his old starlet, and new wife.

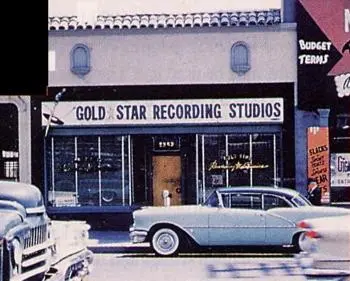

For Ronnie it had been clear very early that her dalliance with Phil would be a Faustian bargain. Not until many months after finding those women’s shoes had she learned – dragged into the Gold Star ladies’ room by Darlene Love to get the ominous news – that he was, in fact, already married. Sensing that her career and his guilty obsession with her were inextricably linked, she made the decision to shut her mouth and press forward. But the latter, it turned out, would outlast the former. Phil’s divorce from his first wife freed the lovers from secrecy but only hastened his descent into a jealous frenzy. Ronnie’s role was steadily diminished, her public appearances steadily constrained. When the Ronettes were tapped by the Beatles to be the opening act on what would be their final tour, he declared that their lead singer was needed in the studio and gave her spot to her cousin Elaine.

By then, just two and a half years after they’d romped around London together, the cultural chasm between these two acts was plain. By letting slip that spring that the Fab Four were “more popular than Jesus,” Lennon had not only turned that tour into a PR nightmare, he’d also indirectly sealed the group’s farewell to live performance (and given his critics what would, in the case of Mark David Chapman, turn out to be fatal ammunition). Meanwhile Nedra of the Ronettes had not only found Jesus, but had married a man who’d soon whisk her off to start a community for Jesus freaks in upstate New York. While girl groups were still nominally alive and well, the punkish intensity of the early sixties had given way to the smooth polish of the Supremes: another necessary step in the culture’s lurching dialectic progress. By a few months after the tour, the Ronettes were no more; their last single, the wistful “I Can Hear Music,” had peaked at #100.

Phil’s handling of them had become ever more arbitrary and dysfunctional, and Ronnie had begun to suspect that he was, consciously or not, out to sabotage her career. Records that they slaved over together during that last year or two might or might not ever see the light of day. Some would be released years later, revealing some of her finest and most emotional work: “Paradise,” for example, a poignant Wilsonesque fantasy about escaping to a land where “time is standing still and lovers fill / The quiet places by the shore.” None is more haunting than “I Wish I Never Saw the Sunshine,” in which the Wall of Sound collapses into an impenetrable, nearly amusical morass shaken by a savagely pounding Hal Blaine beat. From somewhere in this unearthly landscape an imprisoned Ronnie pours her heart out, her gorgeous, anguished vocal for the first time betraying grief and regret.

Soon enough the prison would be all too real. Phil and Ronnie marry in 1968, and with his possession of her finally complete, he sets out to make it permanent by locking her into the twenty-one-room mansion on La Collina. The story of the next four years emerges in ghastly snapshots. Rare solo outings in the car, accompanied by a protective life-sized doll in her husband’s likeness. Coming downstairs at Christmas to find a set of twins, adopted by Phil as a horrific surprise present. A solid-gold coffin with a glass lid, which he claims he’s had made as her final resting place, should she ever attempt to leave.

Leave she finally does, somehow, before her deepening alcoholism or her husband has done her in – escaping barefoot, with nothing, onto the streets of Beverly Hills. To Phil it is the crowning insult. He can only convey his rage through his alimony payments, which he sends entirely in dimes, or as checks with FUCK YOU scrawled on the back. But even twenty years later we find him spitefully campaigning the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame to exclude the Ronettes, and succeeding until his own death.

Phil’s own career manages an unlikely second wind, thanks to the disintegrating Beatles, who by this point have little in common apart from an unflagging, nostalgic admiration for the Wall of Sound. He’s the only person they can think of to entrust with pulling the shambles of the Let It Be film soundtrack into a coherent album, and though his heavy hand infuriates McCartney, he parlays this into jobs producing the first solo efforts of Lennon and Harrison. Later in the seventies he’s sought out by Leonard Cohen and the Ramones, who find in his work enough erratic bursts of genius to make up for his demented studio behavior – which features lots of brandishing, and occasional firing, of guns.

For his many female acquaintances through the remainder of his days, the story is much the same. They meet what seems to be a charismatic starmaker, and find within him a mangled, abandoned, terrified child. Several will report having guns pulled on them when trying to leave his home, which is now a turreted castle on a hill, miles from Hollywood, looming fantastically over the featureless suburb of Alhambra. And eventually, in February 2003, one of those guns will go off – in the face of Lana Clarkson, an actress working at the Hollywood House of Blues while doing everything she can think of to revive her career. In his trial, Phil claims that she asked to “kiss” the weapon. But her purse was already on her shoulder; like so many before her, she was looking for the exit.

He still wields enough power to stall a verdict for six full years, but not, in the end, to save himself. Spector spends the last seven years of his life in a prison hospital, his voice destroyed by tumors along his airway, serving out 19-to-life for murder in the second degree. It’s COVID that finally gets him.

As for Ronnie, back in 1972, she’s at rock bottom – but still, somehow, in possession of a few embers of the inner fire that had carried her out of Harlem and into the hearts of America. She finds her way back to New York and sets about picking up the pieces of her shattered career, without having much idea of where to start. Then one day on the Upper West Side she hears a familiar scouse accent from behind: “Ronnie. Ronnie Ronette.” It’s John Lennon.

John’s got a baby now to take care of, but he puts her in touch with a few people. She’s amazed to discover the resonance that her name and her music still have with a new breed of old-school rockers. The chance meeting leads to collaborations with the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Joey Ramone, Eddie Money. Just like Ronnie sang, says Eddie, and trusts his audience to understand.

She marries again, eventually, and does it right. She gets a quiet place in Connecticut, just down the road from old pal Keith Richards, who inducts the Ronettes into the Hall when the time finally comes. By then Estelle’s a shell of herself, unable to perform, having wrestled with schizophrenia, anorexia, homelessness. Nedra’s a grandmother whose husband is busy producing Pat Robertson’s The 700 Club. But they pull off “Be My Baby” one last time, and crush it, with an adoring Paul Shaffer leading the band.

She’s got a couple of kids now and has settled into a suburban life that she happily describes as boring – by day. But on show nights, as she gears up to get back on stage, the fire rekindles and her “heart starts beating like crazy.” She does her signature song every time, and every time her ecstasy is real, every time that boom, boom-boom, BLAM sweeps her away.

I don’t do regrets, and I ain’t bitter. As I get older, I think maybe everything in life was meant to be. The way I look at it, I’m still here. I’m still singing. People still love my voice. And I made some great pop records, songs that people hold in their hearts through their whole lives. Ain’t nobody can take that away from me.

The very last session at Gold Star Studios, in 1984, featured Maurice Gibb of Bee Gees fame. Mo was recording a film soundtrack and was excited for the opportunity, having worshiped the Spector records as a teenager; he remembered staring at the ceiling during late nights with his brothers, halfway around the world in Sydney, Australia, wondering what that fabled echo chamber might look like. Dave Gold and Stan Ross had kept it jealously locked against outsiders for thirty years, but figured it wouldn’t hurt to bid it a proper farewell.

To get in, you had to track down the key and a flashlight, then wedge yourself through a series of doors about two feet square, as though penetrating the pyramid of Khufu or the great cavern of Lascaux. At the end of this passage Gibb found himself in a narrow, bare gray room about eighteen feet long. A modest speaker and microphone were the only furniture. Breathing in there felt funny, and voices sounded weird, ominous. Looking up at the trapezoidal ceiling, he had the uncomfortable sensation of being in a coffin.

Shortly after the session wrapped and the studio closed its doors for the final time, Gold and Ross got word that a fire had somehow broken out in the abandoned building. A bizarre coincidence, though maybe Brian Wilson would have seen it differently. They went out the next Sunday to assess the damage, and found only the echo chamber still standing, like some kind of tomb.

Perhaps that’s one way of seeing “Be My Baby”: as a mausoleum, a splendid, forbidding Taj Mahal of a structure, still standing amidst a desecrated landscape. It reflects Spector’s mad drive not merely to possess innocence but to embalm it, entomb it – to awe the world with its resplendence, while ensuring that its spirit could never again leave and betray him. But again I catch myself at that word innocence. It is not the right word for what “Be My Baby” is about. Nor is it the right word for the “true magic” of the Gold Star echo in which Neil Young lost himself. Or the “sweet thing” that Brian Wilson watched die. Or the “sunshine” that Ronnie wished she never saw. Or the memory, at the heart of all memories, that lost its meaning for John Lennon.

–

1 Why major and minor chords affect us so differently has been debated for centuries. Summoning sadness through a C chord by simply changing an E to an E flat is, on the face of it, one of the most mystical powers that music wields. But there’s some recent evidence that that subtle difference jibes with emotionally laden differences in our speech patterns, as we express ourselves in more excited or more subdued ways. In other words, we’re predisposed to hear a minor third as sad because sad people actually use it – though we’re rarely, if ever, conscious of processing these patterns.

2 “Be My Baby” is actually in the key of E. I’m moving it to the key of C here for the sake of simplicity, since thinking in terms of the white keys comes most naturally to many of us who’ve had a piano lesson or two. When analyzing the harmonic relationships in the song, it makes no difference.

3 The circle-of-fifths variant with all-major or all-seventh chords is also known as the ragtime progression, honoring its popularity in jazz’s forerunner. “Sweet Georgia Brown” is a familiar example from the first quarter of the twentieth century.

4 A mention must be made here of “I Got Rhythm,” another musical-theater number written several years earlier by George Gershwin. Though the progression is exactly the same as in what would become “Blue Moon,” “Rhythm” is a jaunty tune with changes so rapid that the listener can’t really register their emotional affect. (Ironically and tellingly, its lyrics tell the exact opposite tale from that of the ice-cream ballad: “Who could ask for anything more?” repeats the narrator, her self-satisfaction emphasized by the chords landing firmly on I at the close of their fourth go-round.) That makes the sped-up pattern fairly useless for the essentially sentimental discourse of pop, though it became so pervasive and foundational in jazz that it soon became known as “the rhythm changes.”

5 “Complicated” has the distinction of featuring both I-vi-IV-V (verse) and I-V-vi-IV (chorus). For Lavigne’s writing/production team (a neo-Brill-Building outfit called The Matrix), tasked with crafting a debut single for a 17-year-old “anti-Britney Spears,” this is a canny way of underscoring the step toward maturity.