Introduction

This is a detective story. It’s the story of one of the greatest mysteries of all time: a mystery so great that it took generations upon generations of the world’s cleverest minds, each building on the work of the last, to finally solve it. A mystery so great, in fact, that solving it has turned the whole world on its head.

In the beginning, there were only scattered clues. There were rumors of ordinary objects with extraordinary powers, pushing and pulling each other invisibly across empty space, in ways that could only be chalked up to magic. There were strange stirrings of nature, spectacles unfolding against stormy skies and over churning seas, that could only be chalked up to the anger of the gods. There were claims of weird, monstrous creatures, too, armed with weapons so mysterious and deadly that they could only be supernatural. Few people even guessed that these clues might have anything in common – aside from seeming to point to some secret, unknowable dimension beyond our own.

But as time went on, superstition gave way to curiosity and doubt. A new breed of thinkers started hunting for patterns, tracing connections, questioning and guessing and testing. They learned when to expect the mysterious force to show itself, and where, and in what quantities. They learned how to command it for themselves, first in faint, fleeting bursts, then in formidable stockpiles, and later in tremendous rivers of energy powered by gargantuan machines. This book celebrates those sleuths, from the ancient Greeks all the way down to the theorists and tinkerers who revolutionized modern technology.

The solution to the mystery turned out to be stranger than anyone could have imagined. When at last it began to take shape in the 1800s, it struck many people – even some of the world’s leading scientists – as sheer fantasy and nonsense. It was as though Sherlock Holmes, hot on a killer’s trail, had gone looking for a gun-toting villain and instead found a troop of invisible gremlins. But the evidence now is overwhelming: electricity really is that strange.

We know now that electricity is the surfacing of one of the deepest, oldest, and strongest powers in the universe: a force trillions of trillions of times stronger than gravity, capable of reaching its mighty hands across infinite distances, through empty space or the densest matter, at nearly instantaneous speeds. We know that what we can see and wield is only the slightest flicker of this force (the electromagnetic force), the barest finger-twitch of a sleeping giant of unimaginable size. That giant’s sleep rests upon an ancient and delicate balance of charges, a stalemated tug-of-war between armies of positive and negative.

Because of this balance, we are only rarely aware of the electromagnetic force like we are of its weaker cousin, gravity. Yet it is the glue that holds our bodies together, along with everything else in our everyday world. Without it atoms could not form molecules, molecules could not form cells, and the universe would be a formless, lifeless wasteland.

Not only does the electromagnetic force give us our form, but it gives us our energy, too. In the giant pressure-cooker at the Sun’s core, millions of tons of careening atoms crash in to each other each second and are fused together. These intense reactions send waves of electromagnetic energy hurtling into space – where, eight minutes later, the Earth’s plants harvest it as sunlight and the food chain is begun. Without the light and heat from these reactions, our planet might as well be Pluto. When the first scientists and inventors began playing around with electricity’s curious effects, little did they suspect that they were summoning such a fantastic power.

In this book you will read about dead men brought to life, about super-powered children moving objects with their minds, and about flaming omens from heaven. You will read about bloody wars and star-crossed love, about paupers who rose to the stature of kings, and about ordinary mortals who learned to wield the power of sorcerers. These things may seem better suited to fairy tales than to the history of science – and today, of course, we have perfectly scientific explanations for all of them. But it is easy to take those explanations for granted, and to forget how mind-boggling the truths themselves were as they were being revealed. In some ways, rather than studying how we make sense of them now, we can learn more from how people understood and responded to them in the past.

As you have already figured out, this is not a textbook. Your average textbook, when tackling a complicated subject like electricity, will take what we know about that subject for granted – as one great big body of fact, to be broken up into logical pieces. Instead, this book pays tribute to the uncertain, messy, human process by which we uncovered that body, piece by piece. It pays tribute to the many wrong turns along the way, the misguided theories and failed inventions that paved the way for the great successes to come. Sometimes approaching a subject this way – putting human faces to the names, and flesh to the facts – makes it easier to engage with it. Sometimes understanding a subject’s life story – the real process by which science wrapped its mind around it – makes it easier to wrap our own minds around it.

One more thing. I said in the beginning that we have solved the mystery of electricity. But this was not the whole truth, for there are pieces of it that still have not been solved. I will mention a few of them towards the end of the book. Perhaps, after reading it, you will decide to take up the challenge.

1. The Lightning-Stone

Miletus, Asia Minor, c. 600 BCE

There once was a great god, Perkūnas, who ruled over the thunder and the lightning. He had a daughter, a sea-goddess who lived in a palace made of glittering amber on the ocean floor; her name was Jūratė, and her life was beautiful but lonely.

It came about that she heard of a fisherman, a mortal, who was casting his nets into her waters without her blessing. Jūratė sent her mermaids to order him to stop, but he only ignored them and carried on. Furious, the goddess rose to the surface to confront the man. Yet no sooner had she laid eyes on his handsome face than she had fallen helplessly in love. She carried the man, Kastytis, to her palace, and there they lived in happiness.

But when her father learned of her crime, he was filled with anger. He flung his thunderbolts into the sea, shattering the glorious palace into a hail of shards. Chaining Jūratė to a rock amidst the ruins, he left her to weep for her sins.

Whether she sits there still, no one knows. But if you walk Kastytis’ shore after a winter’s storm, you will still find washed-up shards of amber, flashing with the fire of the angry god.

Those shards proved valuable indeed for the people who knew where to find them. They gathered the amber in nets and baskets, and sent it by cart and boat along the great rivers of Europe. Along the bustling shores of the Mediterranean there was great demand for the strange little stones, like jewels but light enough to float and soft enough to burn, with a scent as rich as incense. The “gold of the north” was made into jewelry for the pharaoh Tutankhamen, and was offered to the gods at the great Greek temples. Eventually, a piece of amber made it into the hands of a very unusual man.

Thales of Miletus was not inclined to believe any stories of gods and sea-castles. He had seen and heard too much for that. His hometown, on the coast of what is now Turkey, was one of the liveliest cities in the world. Rich winemakers from Athens rubbed shoulders with Babylonian merchants, while sailors returned from Spain, Egypt, and the Black Sea with silver and fish and papyrus, along with stories of strange peoples and mysterious knowledge. Tall tales flew at the taverns and markets, but so did business schemes – for Miletus was among the first cities to have money in the form of metal coins, and everyone wanted a share.

Thales was a successful businessman himself, with plenty of time to think. (Sometimes he thought so much it got him into a trouble, like the time he fell into a well while staring up at the stars.) Lately he had taken an interest in a different kind of currency: a currency of the mind. What if, instead of just re-telling the old stories about gods and magic, we used our powers of reason to figure out how the world worked? Could logic cut through the differences between languages and cultures, like the ones that jostled against each other at the Miletus harbor, and get at the universal truths of nature?

Hungry for knowledge, Thales learned everything he could. He learned about geometry from the Egyptians, and about astronomy from the Babylonians. Instead of taking what he learned for granted, he pushed it to the limit, coming up with new theorems and conjectures of his own. He figured out how to measure the distance to ships offshore, and he shocked his neighbors by predicting a solar eclipse. But these were just clever tricks compared to his biggest and boldest idea.

It went like this: behind everything that we can see and touch, there exists one single universal substance, or force. Take things apart into their smallest bits, Thales said – living and non-living things alike, from sticks and stones to the human body to the sea and sky themselves – and you will find that they are all made of and moved by the same stuff. This idea was so big, in fact, that in one fell swoop it founded all of science and philosophy as we know it. In a way, more than two millennia later, our most brilliant minds – those working in particle physics, for example – are still working to answer the questions raised by Thales’ idea.

Thales was the sort of man who noticed things. And so when he overheard a conversation about amber and its magical properties, he promptly decided he needed to see for himself. He went down to the market and picked out one of the many stones for sale. It was pretty, but didn’t seem especially magical. He shrugged and put it in his sack. Later, at home, he took it out. And then something strange did happen.

He had reached out to set the amber on a table next to a pile of straw, and out of the corner of his eye, he saw the straw move. Thinking at first it was only the breeze from his moving arm, he waved his hand in front of the straw again. This time it was unmistakable: the straw was moving toward the amber, as if it were pulled by an unseen force!

He sat down and began to experiment. After a short time, the amber seemed to lose its power. Yet he discovered that if he rubbed it again with the fabric of his bag, that power was restored. It was able to attract many lightweight objects, such as pieces of paper and bits of wheat chaff. Sometimes he even heard and felt a faint spark, as though tiny bolts of lightning were leaping between the stone and the things that fell under its sway. Truly it did seem magical – but for Thales, it was simply a vivid demonstration of the mysterious, but natural, force that animates the world.

There were many questions that he was unable to answer. What was special about amber that allowed it to “use” this force so powerfully? And what was happening to it when he “recharged” it with the fabric? If the fabric was passing the attracting force to the amber somehow, then why did it not attract things to itself? As it happened, these questions would have to wait thousands of years for an answer. But thanks to his willingness to raise them – and to search for his own answers, rather than blindly accept the old mythical ways of thinking – Thales had discovered something extremely important. In fact, all these ages later, its name still honors his discovery. For the Greek word for amber, the lightning-stone, was elektron; and our word for Thales’ mysterious force, which powers the world in ways he could not have imagined, is electricity.

2. A Shock from the Sea

Island of Capri, Roman Empire, c. 30 AD

It was no secret: the beautiful clifftop palace, perched high above the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean, was in truth a house of horrors. This was the private retreat of the Emperor Tiberius, an ugly, sulking, paranoid man, who had built it after fleeing his responsibilities in Rome. Rumors flew about just what went on behind those walls. Enemies of the Emperor were tortured in unspeakable ways, some said, before being thrown from the cliff to their deaths. Children were torn from their families and enslaved, and forced to serve Tiberius’ every awful whim. Meanwhile, members of the useless Court lounged around the grounds, fattening themselves on meat and guzzling wine by the gallon.

One of those members was a man named Anteros, who must have remembered a much simpler life. He had been born a slave, but when his hard work and intelligence were recognized, he was freed from bondage so that he could better serve the Empire. Rising up through the ranks, he eventually reached the position of Procurator of the Inheritances. It was a powerful position indeed, as he controlled all the money that had been passed down to the Emperor through the royal family. What he thought of Tiberius himself, or of the bizarre lifestyle at his new pleasure-palace, we do not know. But we do know that he suffered from it in one way. Thanks to all the rich foods and wine in his diet – possibly spiked with poisonous lead, from the cauldrons in which the wine was boiled – Anteros had a bad case of gout.

Gout was so common among the Roman upper class that it became known as the “rich man’s disease” or the “disease of kings.” Caused by an excess of uric acid, which builds up in the joints faster than the body can pump it out in the urine, it drove its sufferers to agony. Flareups felt like being stabbed with a million icy needles, and they were often worst in the middle of the night, when there were no distractions. On this particular night, as on so many others, Anteros woke up with his big toe seemingly on fire. Grimacing, he waited for the pain and swelling to die down, only to find that he was wide awake. Perhaps a walk on the beach would help, he thought.

The pain came and went as he picked his way carefully down from the dark cliff and set out across the sand. When he reached the water, the coolness of it provided some relief. But he had hardly gone a few yards when he was stopped in his tracks by a very different feeling altogether.

With a jolt that seemed to paralyze his whole body for a moment, the soreness in his foot was suddenly replaced with a fiery tingling, and then an overwhelming numbness. Within a split-second it had traveled up his foot into his leg, and before Anteros regained his senses enough to yank it back, his entire leg was numb. He felt as though he had been struck by lightning. Gaping at the water while he held his useless leg, he saw a shadowy form glide slowly off into the depths. Suddenly he realized what had happened: he had walked right into one of the most legendary fishes of the sea, the mysterious torpedo.

The creature had been well-known, and carefully avoided, by fishermen for centuries; even its name came from the Latin word for “numb.” (A rival of Socrates had once accused the great philosopher of stunning people like a torpedo with his constant questions.) A type of ray, it was a flat, sluggish animal with bright spots like eyes, and it captured its prey in the same way it defended itself: by shocking them into submission. It didn’t even need to touch them to do so, as whatever strange force it commanded could seemingly “infect” the very water in which it swam. Fishermen had even reported spearing torpedoes and being shocked through their spears, or hauling the fish onto their boats, pouring water onto them, and receiving jolts through the streaming water. If there was any doubt that magic was afoot in nature, surely the “numbfish” set that doubt to rest, with its devilish power to cause pain at a distance.

But as his own shock subsided, standing there in the moonlit surf, Anteros began to feel strangely grateful to this notorious fish. The pain of the gout did not return right away, and in fact, it did not return for the rest of the night. Had he been cured? Awed by his miraculous encounter, he told his story to the Emperor’s physician the next day. And from then on, the torpedo’s legend only grew.

Before long, doctors throughout the Empire were prescribing torpedoes for everything from gout to hemorrhoids. Chronic headaches? Press a live torpedo to your throbbing brow. Epileptic seizures? Add some torpedo-flesh to your diet. According to one remedy, this magical fish could even remove unwanted body hair – provided you mixed its brains with a little salt, and applied it to your skin on the sixteenth day of the month.

There were those who suspected that even though the torpedo’s “dread paralyzing force” could not be seen with the naked eye, it might still have a perfectly natural explanation. At least one Roman philosopher pointed out the similarity between the fish’s power and the attractive force of amber, classifying them both as “un-nameable properties.” But by the time those properties began to give up their secrets, the Empire was long gone. Some say that lead poisoning hastened its fall.

3. A Fiery Omen

Constantinople, Byzantine Empire, 1453 AD

For the fifty thousand bedraggled souls living in what once was the greatest city on Earth, there was little doubt that the end-times had arrived.

It had been coming, some said, for many years. Two centuries ago, Constantinople had boasted a population ten times as large – until it was brutally pillaged and burned during the Fourth Crusade. A century after that, half the city had succumbed to the plague known as the Black Death. Now an enormous army of Muslim Turks was waiting just outside its walls. Not only the city once known as New Rome, not only the ancient empire of which it was the last remnant, but the entire Christian world seemed to be teetering on the brink of collapse.

The siege had been raging for seven weeks now, and desperation was building. The Turks had captured a group of scouts outside the walls, and had put their impaled bodies on stakes for the whole city to see. In response, the Byzantines had marched their enemy prisoners onto the ramparts and executed them, one at a time, in plain view. Food was running short, and the Turks were working furiously to build tunnels underneath the walls. And now, as if to confirm what everyone already knew in their bones, the supernatural omens had begun.

The first was the blood moon. On the bright night of the twenty-second of May, the full moon suddenly disappeared into shadow, and then turned a sinister red. The people of the city were struck with terror. Yet the next day the mood changed again, as two Turks were captured and pressed into revealing the locations of their tunnels. Maybe, just maybe, all was not lost.

On the morning of the twenty-fifth, anxious to lift his people’s spirits, the Emperor ordered that an ancient icon of the Virgin Mary be fetched for a ceremonial procession. The heavy, gilded painting, which according to legend had protected Constantinople for a thousand years, was hoisted onto the shoulders of a team of men and led through a massive crowd. But then, right before everyone’s horrified eyes, the icon wobbled and fell to the ground. The men tried to lift it back up, and failed. Had God abandoned the city in its hour of greatest need?

But as hard as it was to believe, the worst was yet to come. Just as the stunned procession got back underway, the clouds overhead rumbled and a thunderstorm struck. Torrents of rain and hail pelted the scattering crowd, and flash floods soon rampaged through the streets. After a restless night, the city awoke to an eerie silence: dense fog had moved in behind the storms, smothering everything in a pale shroud. The whole day went by in a dazed stillness – until the eyes of the Byzantines were suddenly caught by something flickering above, and the silence was pierced by screams.

Following the pointing fingers, passersby craned their necks up to look at the towering dome of the Hagia Sophia. The grandest church in the world and the pride of Constantinople, the building had survived earthquakes, fires, and invasions for nearly a thousand years. But never had it looked like this. The dome was surrounded by a ghostly blue flame – a sight so awful and strange that it brought the Emperor himself to his knees in terror. The unearthly fire flickered and danced as the people gaped from below. Then, before anyone could find the words to speak, it seemed to free itself from the church and go shooting up to the sky.

The Emperor, when he regained his senses, gathered his advisers for an emergency meeting. There was only one explanation, they said, for what had taken place that evening. God, who once had blessed their city with his protective light, had now snatched it back to heaven. There was little use in fighting now. Constantinople was doomed.

Outside the walls, the Turkish Sultan gathered his advisers as well. The signs could not be more excellent, they said. The city’s good fortune had gone up, literally, in flames. Now was the time to attack. Thanking Allah, the Sultan gave the signal to ready the final assault. Three days later, Constantinople was in the hands of the Turks.

Neither side could be blamed for seeing the hand of God in these nightmarish visions. They could not have known that an even more spectacular event had occurred earlier that year: the tremendous eruption of a volcano halfway around the world, on an island in the Pacific Ocean. One of the biggest ever recorded, the eruption had hurled staggering amounts of black ash and stinking gases into the atmosphere, where they were swept off by winds to make mischief with the weather across the globe. Freakish storms, unexpected fogs, and unseasonable cold snaps were among the results – along with even stranger phenomena.

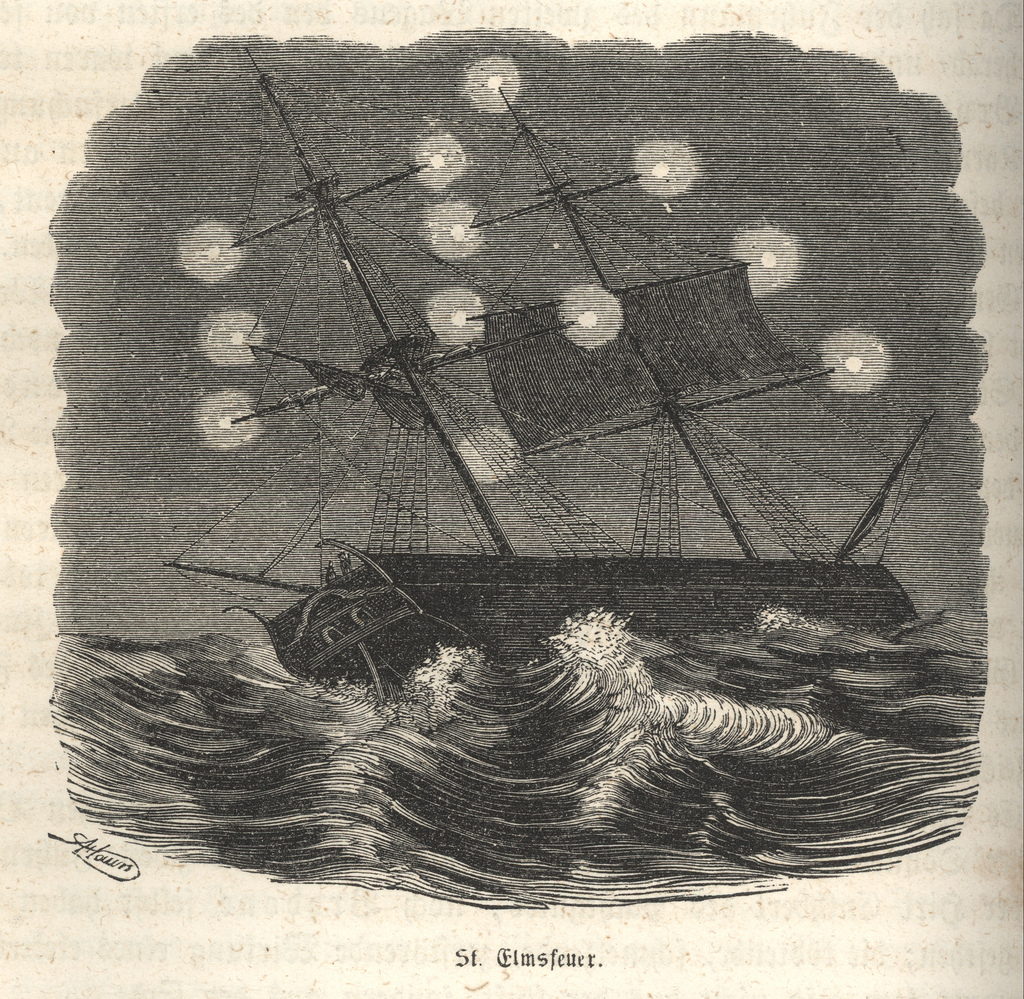

Many of the men of Constantinople, a port city, would have spent time on the sea. The dancing light on the Hagia Sophia may have reminded a few of them of a time-honored subject of sailors’ lore. Before and after storms, when the air seemed fraught with nervous energy, a blue light sometimes appeared around the masts of ships. Though it went by many names, the best-known was St. Elmo’s fire, after an old Christian saint who had once bravely finished giving a sermon to a group of sailors after lightning struck the ground beside him. The sight of the fire was seen as a good omen – a sign of St. Elmo himself reaching down and blessing the ship with his supernatural protection.

The fall of Constantinople was one of the great turning points in history, and the vision of the blue flame helped turn the tide in that direction. But although the Byzantines could see only an apocalyptic ending and a fall into darkness, there was a new kind of light on the horizon, too. Many of the city’s greatest minds were able to escape its ruins and flee to Italy, where they helped usher in a new age known as the Renaissance. The medieval days of myth and superstition, of waiting for signs from God, were coming to an end. In their place was a new hunger for knowledge about nature, much like that in ancient Miletus.

The fire of St. Elmo, the power of amber, the jolt of the torpedo – these were still just wondrous curiosities, with no known connection aside from their utter mystery. But that would soon change, and change fast.