In François Rabelais’ novel Gargantua, written in the early 16th century, the titular giant travels to Paris and soon tires of all the little “boobies” crowding in for a look. Taking a breather against the towers of Notre-Dame, he decides to present an offering to the city — but one after his own, extravagant fashion:

Then smiling, he unfastened his noble codpiece and lugging out his great pleasure-rod, he so fiercely bepissed them that he drowned two hundred and sixty thousand four hundred and eighteen, exclusive of women and children.

By sheer fleetness of foot, a certain number escaped this mighty pissflood, and reaching the top of the Montagne Sainte Geneviève, beyond the University, sweating, coughing, hawking and out of breath, they began to swear and curse, some in anger, others in jest:

“God’s plague and pox take it!”…”Das dich Gots leyden Schend!”…”Pote de Christo!”…[etc.]

Though the damage seems catastrophic, the piss of Gargantua proves unexpectedly restorative. (It’s not the only time; elsewhere we hear of him urinating for “three months, seven days, thirteen hours, and forty-seven minutes” and thereby creating the river Rhône.) Wrapping up the scene, Rabelais notes casually that this was in fact how the great city got its name: from the giant’s motive for drowning it, namely, par ris — for a laugh.

What good is mere laughter? Rabelais, for whom par ris could have served as a motto, had strong feelings about this. In the works of this mischievous monk, humor — the bawdier the better — serves time and again as purifier, fertilizer, regenerator. Ultimately it burst the floodgates of an entire literary tradition: in Milan Kundera’s poetic take, the writer of Gargantua simply “heard God’s laughter one day, and thus was born the idea of the first great European novel.”

Like us, Rabelais occupied a society that was anxious for rebaptisms (though perhaps pissfloods were not what they had in mind.) Like ours, his was a time of confusions and dislocations, a time when the old foundations of human dignity found themselves suddenly battered by strange tides. Columbus’ “discovery” of another hemisphere, and Copernicus’ marginalizing of the Earth itself, had punctured Europeans’ sense of self-importance. A new economic system, one of dizzying fluidity and abstraction, was toppling the old feudal order, and with it came a shuffling of cultures and castes that challenged privileges and bred new strains of distrust. Political power dwelt increasingly in distant seats of government, rather than within self-sufficient estates; religious authority belonged increasingly to esoteric elites in distant academies; the Catholic Church itself, to which Rabelais stayed true even while lampooning it ferociously, had grown so ponderous, arcane, and corrupt that the cracks of religious schism were widening throughout Europe.

In short, the world was ruled, arguably more than ever before, by men who dealt in abstractions. Characteristically, Rabelais coined a new word for these people, whose greatest sin in his view was forgetting how to laugh. He called them agélastes, from the Greek, and regarded them with terror and disgust. In return, they doggedly persecuted him and his unruly books. (He was forced into hiding for a time, but avoided the fates of several of his writer friends; at least one of them, Étienne Dolet, was burned at the stake for heresy.)

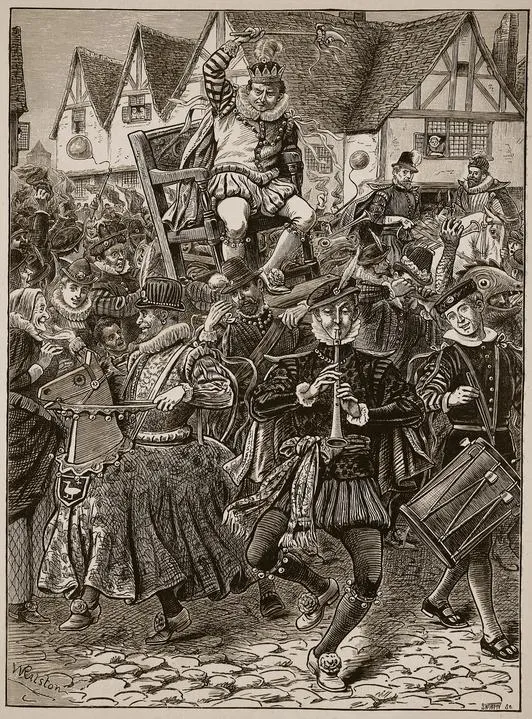

What troubled the Church most about Rabelais was that the torrent of oaths, puns, dirty jokes, tall tales, and general anarchy that filled his pages had a potent natural wellspring. For millennia, communities had been carefully devising ritualized outlets for this pent-up uncouth energy. It happened every December in Ancient Rome, during the Saturnalia festival, when masters served their slaves amidst general gluttony and drunkenness. It happened every January in medieval France, during the Feast of Fools, when a random peasant was appointed “Lord of Misrule” and clergymen rode in dung-carts flinging feces at the revelers. These eventually evolved into Carnival, with its masks and mocking costumes, its staged battles and pageants of sex. What these rites all had in common were a merry obliteration of rules and upending of hierarchies, and an emphasis on liberating the base impulses: the profane, the scatological, the violent, the libidinous. To a modern observer, they might have looked like gratuitous, unhinged depravity. But in fact they served a vital social function, acting as checks on the abuse of power, keeping uppity humans and institutions from drifting too far from their shared humanity.

Carnival, in its original state, could never have survived into the modern age. We’re too self-conscious now, and our forms of protest too easily appropriated — so that what once was true participatory subversion becomes, for example, the commercialized spectacle of Mardi Gras. But the carnivalesque mode, of which Rabelais was the grand master, has persisted in our art and literature. It flourishes whenever and wherever societies grow too top-heavy, too dislocated, too out-of-touch. If you’re a sentient being in the year 2016, those adjectives likely ring a bell.

—

Of all the scary things about this year — and truly it’s been a smorgasbord of scary — the scariest, to me, is the gusto with which we’re burning our bridges of dialogue. Everywhere we look we see friend lists being purged, comment threads going nuclear, pundits and public servants veering between professions of bewilderment and bursts of vitriol. We’ve all been alert for years to the entrenchment of antagonistic politics, but our dysfunction this season seems more ominous: there seems to be a widespread abandonment of the will to engage with, or even comprehend, the other side.

But the other side of what exactly? I see a consensus that the cultural chasm before us yawns deeper than anything we’ve seen in at least a generation, perhaps much longer. I see much less of a consensus about how to define that chasm. With populist insurgencies rocking each party, the old left-right spectrum is waning. Democratic and Republican buzzwords are brandished with less righteousness now, as the party of “freedom” goes in for locking down borders and tapping phones, while the party of “equality” is ruled for now by a dynasty of globalized capitalists. Rich vs. poor, black vs. white, open vs. closed, hope vs. fear, tradition vs. progress, faith vs. reason, smart vs. dumb, order vs. chaos: none of these binaries is quite sufficient on its own, while each reveals the assumptions and condescensions of those that pose it.

Of course, if there’s one figure who defines the chasm entirely on his own, it’s the carnivalesque figure of Donald J. Trump. With his careening diatribes, his bathroom jokes, his schoolyard taunts, and his phallic fixation, Trump is nothing if not a trickster figure, a jester in king’s robes. His delight in offending one and all is matched only by his desperation for approval — the hallmarks of a clown. His great, Rabelaisian ambition seems to be to ride into Washington and piss on everything.

Like most of the people who are likely to read this, I instinctively fear and loathe Trump and what he represents. I’m not, however, willing to write off his vast chunk of the electorate — forty-three percent of us, at the time of this writing, which would translate into some fifty million souls — as so many dupes, drones, schmucks and pricks. Of course, it’s not a homogeneous bunch; within its ranks are plenty of apolitical types opportunistically jumping aboard a thrill ride, as well as conventional conservatives pragmatically holding their noses to achieve particular ends, like Supreme Court picks. But there’s a far larger and more sincere group that seems to make up Trump’s core of support: a group to which Trump seems to be speaking like no candidate has spoken before. So I’ve been listening whenever possible to what those people — I’ll call them the Trumpists — actually have to say, and I find I can make the most generous sense of it through an appreciation of the ethic of carnival.

Taking this long view helps me reconcile how Trump can be so clumsy, so craven, so treacherous, so viscerally repulsive to his enemies, and yet command such fascination and hope. I’m convinced that Trumpists, by and large, aren’t driven by ignorance or meanness; they’ve simply given up on the notion of a President improving their quality of life, and so they’re choosing to vote instead for a Lord of Misrule. Their governing institutions and authority figures have become so remote and unaccountable that, in their view, only an eruption of vulgarity — that is, of the most fundamentally human — can restore their dignity. A Trump “presidency” might turn out to be a catastrophe, but from its wreckage they might just piece together what was once theirs. This may sound like a reckless leap of faith, but to them it’s a calculated gamble. Their odds look better this way than any other.

Can you blame them? The globalized economy, long since grown so vast and complex as to resist comprehension — much less control — by any human being, treats them like tiny, abstract bits to be algorithmically reshuffled. Their jobs have, in many cases, been handed over to robots. Their political opinions amount to whispers into the abyss (as documented by a recent study that concluded that “the preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy”). Their rural communities are being gutted by lack of opportunity, and by their insular susceptibility to drug abuse and other modern epidemics; their urban and suburban communities are shifting, arbitrary cultural mélanges amidst which the maintenance of tradition is all but impossible. In an increasingly technocratic society, the relevant forms of knowledge and skill seem increasingly rarefied; facts themselves are generated in such inscrutable ways, and are so routinely twisted to support corporate goals and ideological narratives, that virtually no one has the energy to slog through the latter to reconstitute the “truth.” Simply making coherent sense of one’s own world has become a task that demands a near-superhuman ability to digest information, resist manipulation, and preserve identity.

Most significantly, the pushers of incremental progress have offered little reason for deep optimism. They fuss around the edges, straightening out an inequity here, expanding a basic right there, but the fundamental threats to human dignity loom ever larger. Income inequality, automation of labor, cultural dislocation, ecological alienation, political disempowerment — these are here to stay, barring radical, violently disruptive changes to our prevailing systems. Beyond all these lurk even more disturbing specters, dimly grasped potentialities of genetic engineering and artificial intelligence, about which politicians are largely silent. The forces pushing us toward them are as subtle and strong as an undertow.

Against this, what does the Trumpist offer? It can be hard to descry any positive vision behind all the invective, but most when pressed seem to fall back on the traditional conservative ideals: small, close-knit communities bound by common cultural traditions; meaningful, unalienating work; space to roam, physically and expressively. They want to be nourished by roots, and they want their limbs left unpruned. And they want, of course, the assurance that these privileges will be kept safe. Their radicalism, such as it is, stems not from any outlandish underlying politics, not from any fundamentally ambitious or vengeful impulse, but rather from their uniquely grim view of our cultural predicament. (Again, this applies to the relatively silent Trumpist majority, not the opportunistic hatemongers that get the most air time.)

As for Hillary Clinton, with her labyrinthine establishment connections, her calculated, unspontaneous style, and her intermittent tendency to dissemble and condescend, she lends herself all too well as an avatar of everything the Trumpist distrusts. The endless harping on her dress, her voice, her manner, the endless exaggeration and fabrication of her transgressions — all of this is brutally sexist, but it also emanates from the belief that she is fundamentally artificial. That is to say, she’s been shaped so thoroughly by inhuman forces — Ivy League intellectualism, corporate opportunism, party-politics machinations — that her human influences, and therefore her legitimacy in speaking to and for the rest of us, have been forfeited. To the Trumpist she’s an agélaste, a humorless, soulless abstraction.

Foregrounding this helps explain the double standard that so frustrates and bewilders liberals. When Trump misspeaks, when he offends, when he tells half-truths or quarter-truths, it’s a refreshing proof of a vital, fallible humanity. When Clinton (or Obama, to a degree) does the same, it’s an uncanny glimpse at the machinery behind the curtain. When Trump takes a stance, however inconsistently or outrageously, it’s seen as emerging from a human brain. When Clinton takes a stance, it’s seen as the final click of a vast, incomprehensible system of cogs. The difference is so profound and preeminent, to the Trumpist, that it steers this entire campaign, leaving all quibbles over platform and character in its wake.

Invoking the carnivalesque also helps explain the Trumpist’s obsession with political correctness. Remember that when Gargantua unleashes his piss-flood, he also unwittingly unleashes a flood of profanity from the startled Parisians. The oaths seem to pour from their mouths uncontrollably, micro-transgressions of the established code of conduct, reasserting the creative and destructive forces that reside within the individual. The mixture of anger and glee that Rabelais describes must be familiar to anyone who’s watched the outpouring of vulgarity at a Trump rally. These are people whose power, they feel, has been slowly sucked away from them for decades. The sacrifice of their political and economic power was not enough; now they are losing their authority over their very speech, watching as it’s uploaded into a hazy Cloud, where it must pass inscrutable tests and satisfy distant, unfamiliar persons in order to gain legitimacy. To regain that power, however fleetingly, is intoxicating. Thus the content of what they utter is not the important thing, and they’ll often walk it back, or qualify it, in a less heady context. The slur, the taunt, the threat — these are just ventings, they feel, of the common air that animates us all: always filled with vapors both sweet and sour, but grown rancid, lately, with suppression.

Our shame over our unfiltered expression in some ways mirrors the shame felt during Rabelais’ time, and policed by the Church, over all things bodily. Just as the medieval faithful practiced mortification of the flesh, so we have our rituals of penance for excesses of speech: trigger warnings, public statements of apology, suspensions of social-media accounts. Small wonder then that those urges should seek alternative, Rabelaisian channels toward the surface. Small wonder that savvy Internet trolls now paint themselves as latter-day heretics, draping themselves in the mythic mantle of anti-hegemonic resistance.

To characterize Trumpists as anti-establishment, then, is to euphemistically trivialize the issue. It’s not merely that they’re opposed to a particular group of people who have governed ineffectively. When they themselves speak of the “establishment,” they’re referring to a new and singular type of entity, one that is invisible, indefinitely vast and complex, and fundamentally inhuman. Like Skynet in the Terminator franchise, it’s an entity that’s been spreading under our noses via infection and self-propagation, stealthily networking itself into self-awareness, and unbothered by scruple in its hunger for planetary control. Once you accept its reality, there is no limit to the evils of which it seems capable, and therefore no limit to the problems for which it can be blamed.

It’s becoming a common rhetorical move on the left to mock the fear that seems to motivate these people. Much less common is the acknowledgement that beneath the superficial fears — of black thugs, job-thieving “aliens,” blaspheming gays, vengeful Muslims — lies a far deeper, less dismissible horror, and one that we all share to some degree. The question it poses is: Will we humans go on being what we’ve been, or will we be something fundamentally different? The chasm that matters, the fault along which civilization will quake over the next century, is between the organic and the synthetic. The claims of the organicists will often be defiantly ignorant and crude, they will often mutate into bigotry and xenophobia, and they will often stand in the way of benign incremental change. Yet to mock or ignore them, it seems to me, would be a calamitous mistake.

I may seem to be defending the Trumpists, and I am, in a way. I sympathize with many of their motives, some of them intensely, and I’m disturbed by the contempt with which they’re treated. But I also think they’re dangerously wrong in some of their assessments. I think they severely underestimate how much the world has already changed, how deeply we are all globalized now, and how little there is to be gained from trying to retreat. I think they overestimate their own purity of thought and motive, failing to appreciate how often their fantasies, whether nostalgic or paranoid, are themselves the blooms of media-borne germs. And I think that Trump himself, apart from making a disastrous president, would even make a lousy Lord of Misrule. Notoriously squeamish, congenitally rich, beholden to shadowy foreign interests, he is not the earthy, transparent, uncompromised, self-propelled force of nature that I suspect his supporters crave. If Trump is our best available champion of the Human, then we are in dire straits indeed.

There is something of urgent importance to learn from him, though. There is an arrogance behind the Trumpists’ exaltation of their own “common sense,” and their stubborn dismissal of other points of view; but there is also an arrogance behind the globalizers’ blithe dissolution of the old rules, and their assumption that the human race will simply catch up to the new ones. From Brexit to ISIS, the weeds of resistance are springing up everywhere through cracks in the cosmopolitan pavement. We need to be able to make sense of our worlds again; and the unsettling prospect before us is that, in order to bridge that gap, it will be us who must be remade.

What of our political future? Democrats these days (and masochistic Republicans, for that matter) often fancy that the GOP is in terminal disarray. I think it’s likelier that the party is in the process of realigning itself to track the fault line that Trump has uncovered. If they succeed, might they make inroads into the massive bloc of disaffected young Americans who feel that their economy has delivered on its shiny promises with fool’s gold? Might they consolidate the growing ranks of science skeptics, for now an unusually bipartisan bunch, who have come to see vaccines, GMOs and the like as Trojan horses for the worst abuses of globalization? If President Clinton sends the military on an ill-advised foreign adventure, might a Trumpist isolationism prevail by evolving into a platform of peaceful restraint à la Eisenhower? Surely the bigotry that has so grotesquely disfigured this year’s campaign will subside; millennial Republicans are a relatively inclusive bunch, according to polls. If I were among them, my fondest hope at this point would be for a Trump presidency to clear the path for a newer, sleeker party, one with a bigger tent and a sharper focus. Given the epochal changes that lie ahead, there would seem to be a comfortable long-term niche for a platform that emphasized humility, self-reliance, continuity, and order.

It may be comforting, or not, to recall that versions of this fight have been fought before. The doctrinal disputes that raged as Rabelais was writing may seem quaintly esoteric to us now, but they were only surface cracks. What ignited them into the wars of religion that shook Europe over the next century-plus was their exposure of the far deeper fault lines of human nature: lines between flesh and spirit, between freedom and safety, between the optimistic and pessimistic self-image. Those lines are coming into sharp definition once more. The difference is that the scope is planetary and the stakes stratospheric. A shiver here now resonates all but instantaneously, in historical terms, on the far side of the trembling globe. Trump sure won’t fix that, but wishing him away won’t either.